Nick St.Oegger

Nick St.Oegger is a documentary photographer whose work explores the relationship between people and places. A quiet American, as he calls himself in his social media, he has been working in Western Balkans since 2013. In Albania, he has a large body of work about a very sensitive issue: the construction of hydropower projects in the rivers of the region known as the “Blue Heart of Europe”, and the impact they have on the rich biodiversity and the unique culture of inhabitants. Here we present the interview that Nick St.Oegger has given to TatìSpace.

Nick St.Oegger is a documentary photographer whose work explores the relationship between people and places. A quiet American, as he calls himself in his social media, he has been working in Western Balkans since 2013. In Albania, he has a large body of work about a very sensitive issue: the construction of hydropower projects in the rivers of the region known as the “Blue Heart of Europe”, and the impact they have on the rich biodiversity and the unique culture of inhabitants.

He has been working for different clients including: Patagonia, Vice, Reuters, Le Monde, Libération, Polityka, De Standaard, Nieuwe Revu, Huck Magazine, Caritas Albania, The Calvert Journal, Suitcase Magazine, Point.51, Trip Advisor, Kosovo 2.0, Riverwatch, C41 Magazine, and Culture Trip. He has exhibited his work and published a book on Vjosa River. From one year now, he lives in Albania. I am very happy that he accepted to give an interview to TatiSpace and share his work with our readers. Below is the interview.

TatìSpace: Hello Mr.Nick! First of all, thank you very much for accepting the invitation to be interviewed and sharing your work with us. Can you please tell us more about yourself? Do you consider yourself a travel or a reporter/ documentary photographer? How do you define your photography? How did the idea or interest to photograph in Albania come to you?

Nick St.Oegger:I grew up in California, but have been living and working around Europe for about 8 years now, mostly here in the Balkans, but also in Ireland and the UK. When I was growing up, I thought I would become a lawyer and this was how I prepared my education and what I was trying to focus on. However, the last year at university I had a bit of a crisis where I realized this wasn’t what I wanted to do. I was interested in photography, but it had always been just a hobby, I hadn’t thought about it as a career option until I discovered the work of some photojournalists who worked in the Balkans in the 1990s, in Bosnia, Kosovo and here in Albania. I was very moved by this work, and the idea of using images to tell a story, to raise awareness about different issues facing individuals and communities. So this is how I started out in this field, this was the moment I knew with every bone in my body that I wanted to be a visual storyteller. I do consider myself a documentary photographer, I am always trying to communicate a story or shed light on a particular issue, and for me photographs are the way that I do this, though writing is also important to my work.

I first came to Albania in 2013, on my first trip to the Balkans. I didn’t know anything about Albania before, and I was mainly interested in seeing the countries of former Yugoslavia. I saw Albania on the map and asked some people about it, everyone had very negative responses like “Oh you shouldn’t go there because it’s run by the mafia” or “It’s dangerous, you’ll get kidnapped” or “Why would you go to Albania? There’s nothing to see!”

I thought about these things as I was planning my trip, and I intended to avoid Albania. I arrived in Istanbul, made my way to Athens where I booked a flight to Venice and I would spend some time afterwards on the coast of Croatia. But the morning I was meant to leave Greece, I woke up and the very first thought which came to me was “Go to Albania.” It’s hard to explain, it was like some sort of vision, or fate. So I missed my flight, instead, I got on the next bus I could find to Albania and the rest is history. It was really a life changing decision, that first trip to Albania: I met amazing people, I saw how beautiful and unique this country is but how little the outside world knows or thinks about it. So it was that trip that I decided to focus my attention on Albania and the Balkans, because it’s a region that many people simply don’t understand, even in Europe.

TatìSpace: Here in Albania, you have a large body of work that includes a vast geographical area (from North to South), and a variety of themes (from bunkers to rivers to the Albanian Alps). From these, I can identify two main projects that are very sensitive to the Albanian public interest: “The Lament of the Mountains” and “Kuçedra”. What started out the idea to work on these projects? Was it commissioned or was it a personal project?

Nick St.Oegger: Yes, both these projects are long-term personal projects that I started on my own and then received further support for. Both of these projects started in a rather organic way. When I first came to Albania, I remember taking the bus from Gjirokastër to Tirana, and passing the Vjosa at Tepelenë. I remember the colour of the water; it was like nothing I had seen before. Several years later I was reading a magazine back in the US and I came across a short article about the Vjosa, how it was one of the last free flowing rivers in Europe, but that the government was planning to build dams on it. I realized this was the river I had seen on my first trip, and I felt a strong desire to return, to document the river, the landscapes, the people along its course. Again, it was this sense of fate, I think. In working on the project I now feel this very strong connection to the Vjosa, and whenever I return it feels like visiting an old friend.

Similarly, “Lament of the Mountains” was produced several years later, after I met an anthropologist who was working in the Kelmend region and she told me about the situation of the rivers there; that they are also building these small hydropower dams. She told me about the culture in the valley, how people are still so connected to the land, how they move with their sheep to the high pastures in the summer. I felt like this was another story I had to tell, because for me the mountains are such an important part of Albania, as well as this very strong rural culture and connection to the land.

TatìSpace: In both projects there is an interconnection between the general view (environmental, political, economical) and the personal view (the impact that the projects have on people’s lives). This gives them an intricate beauty. You skip from landscape photography of large panoramas to close up portraits of mountaineers and peasants living near Vjosa. Have you found difficulty approaching this kind of photography? Can you share an episode that impressed you in particular, for example meeting with villagers or authorities? Also, did you have any problems or incidents with groups or individuals that supported the dam projects?

Nick St.Oegger:Yes, that’s right, and I think it is precisely this interconnection that is so unique and important in Albania. Outside Tirana, there are still many places in the country that are very rural, where people are still living rather traditional lives, working with the land. Yes, there are negatives that come from this life, such as poverty and other problems, but I think the way that many people still live with the land in Albania is unique, and people take pride in this work, they feel a strong connection to their land and the history behind it. So for me, especially with these two projects, it is very important to show the people in context of the land, to show that it is not just one or the other that is being threatened, it is both, because of the strong interconnection between environment and people in Albania. And this connection is exactly what is being threatened by so many proposals, whether it’s by the government, or foreign investors.

It can be difficult to approach this kind of photography. I spend a lot of time trying to work in small communities, to gain people’s trust, which is hard to do in Albania. I think there is a lot of mistrust, because of the history with communism, but also the recent history. People are used to foreign journalists coming, they take some photos for a few days, and then they leave. I have always tried to build stronger relationships with my subjects, to try to get to know them as humans first. I always try to return when I can, to give them prints of some of the photos I took of them. Another important aspect for me has been learning the Albanian language, which is difficult, but it has opened up so many doors. I think because the language is so important to people here, they trust me more when they see I am trying to speak to them in their own language.

Probably one of the most impressive experiences was when I stayed with the shepherds in Kelmend during the summer. We migrated with a herd of 200 sheep, I walked 40km with them to their shelter near Lepushë. It was beautiful to spend time with them there, to see the way they care for the sheep and their families, to see the way the children help with everything and how much knowledge they have about the environment, the weather, how they take care of themselves and fix things. Before this, the ‘malësorë’ were a bit of a mystery to me. I only heard some stories and stereotypes, so it was an amazing experience to see the reality of their lives and I was very honored that they gave me their trust and allowed me to stay with them and photograph.

TatiSpace: Your “Kucedra” project has been exhibited and published in a book. Can you tell us something more about it? How do you find this aspect of photography, when projects communicate to the public? Did the project have an impact?

Nick St.Oegger:That’s right, I published “Kuçedra” as a book first in 2018 and I have exhibited the work several times as well. For me it was very important that these photos go into the world in a physical way, not just on people’s screens. Publishing the book allowed me to raise awareness about the Vjosa, and the issues related to hydropower development on an international scale. I was lucky to partner with Patagonia and Save the Blue Heart of Europe campaign, so the book was distributed around the world, including to members of the European Parliament who have been trying to convince the Albanian government to save Vjosa.

Exhibiting the work has also been important, especially the exhibitions in Greece and Albania. For the Greeks it was a chance for them to see something of Albania, which is so close yet so far (a place many of them wouldn’t consider visiting). I had several people look at the photos and tell me “You know, these places could also be here. We are not so different” and this was very nice to hear, given some of the historical conflicts and tensions that exist between Greece and Albania.

It was so important for me to exhibit this work in Albania as well, so that everyday people can see the beauty of their own country in a way that they might not have previously done. It was really a nice experience to speak with people at the exhibition and to see that they have some connection to my work, to see how it makes them consider their country in a different way. That was very important to me, because I want my work to speak to Albanians. I don’t want it to be just for foreigners to see this “exotic” location. I hope that my work also connects with regular Albanians as well.

TatìSpace: Can you share something more about your next projects or exhibitions (if you prefer)?

Nick St.Oegger: I am planning to start writing another book about these last 8 years working in Albania. It will be a mixture of photos and personal stories from my time in the country. It’s something I’ve been wanting to do for some time. I also will have some more work related to hydropower, documenting areas where rivers have been destroyed by dams. So in a way I am still continuing with this work that I started years ago with “Kuçedra”, and it’s good to continue following this issue with hydropower and the effects it has on communities and the environment in Albania.

I hope to also continue with exhibitions, which unfortunately hasn’t been possible during the pandemic, but maybe as the situation improves it would be great to show more of my work both in Albania and abroad.

TatìSpace: Thank you very much for the interview and hope to see more of your work about Albania.

An overview to the main projects of Nick St.Oegger in Albania, “Kuçedra”and “The Lament of the Mountains”. More can be found in his website: www.stoeggerphotography.com

In “Kucedra” series, Nick St.Oegger explores thelast wild river of Europe: Vjosa (in Albania), and the proposed hydropower projects along its route that will alter the flow of the river, harming the rich and unique biodiversity within it and displacing thousands of people due to the creation of reservoirs. A key source of life for numerous endangered plant and animal species – many of which have disappeared from the rest of Europe’s rivers –Vjosa also holds cultural and economic significance for the rural communities along its banks, which once played an important role in Albania’s agricultural industry. Through landscapes, portraits and interior details, he portrays the environment of Vjosa in its natural state, as it faces the threat of being changed forever.

The Vjosa river near the Greek-Albanian border. Despite willingness to declare the river a national park in 2015, the Albanian government issued a contract to build a new hydropower dam at Poçem. The European Parliament has demanded the government to stop the plans for hydropower on the Vjosa, noting the environment damage it would cause. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

Interior Bënça. Locals in the village have protested a hydropower that will divert water from nearby Bënça tributary, which feeds into Vjosa. The loss of water from this river could have severe negative consequences for the agriculture. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

Ronja, a retired teacher in Kuta. Like many in the village, she does not hold title documents for her land, due to the administrative chaos that followed the fall of communism in the 1990s. This would complicate any attempts to claim compensation for land lost in the creation of the Poçem reservoir. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

Përmet, a cultural hub in southern Albania, well-regarded for its traditional music, art and slow-food practices. The Vjosa is integral to plans for growing the areas’s tourism industry, with the river seen as an important draw for rafting and kayaking excursions. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

Bridge over the Vjosa at Novosele, near the delta. Dams would increase riverbank erosion in downstream areas, meaning the already flood-prone delta region could see increasingly destructive flooding events in the future.

Abandoned petrol station on the road to Kuta. The road that links Kuta to the national highway is of poor quality, and has made shipping agricultural products impractical. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

Romina Mustafaraj, government representative for the village of Kuta. Romina has campaigned for infrastructure improvements in the village, including maintenance of flood-prevention systems, and repairs to the main road linking the village to the national highway. However, no investment has been made by the central government. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

Kuta, Village in Mallakaster county. During communism, Kuta was an important farming village, and went through significant development in the first decades of the regime. However, the area has been in decline since the end of communism in the 1990s. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

Mercedes in the village of Kuta, near the proposed Poçem dam. Around 3,000 people living in Kuta and the surrounding area could be affected if their land is flooded by a reservoir. This would mean the end of the area’s agricultural production, the only industry most have known. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

Farm in Kuta, near the proposed dam at Poçem. The reservoir created by the dam would permanently flood agricultural land in the area. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

“Without our land we have nothing”. Ylli and her family raise sheep and grow crops on land that would be flooded by a reservoir. There are few non-agricultural jobs in Kuta, meaning locals could have to relocate from lands their families have lived and worked on for generations. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

Fisherman’s shelter constructed between two communist-era bunkers in the Vjosa delta. Fishing along the river plays an important part in the local economy, and has already been negatively impacted by unregulated practices, such as dynamiting. Furthermore, damming the Vjosa would be detrimental for species such as the endangered European eel, which migrates along the river to spawn. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

Scientists traveling on the Vjosa near Poçem. Because Albania was isolated by the communist rule of Enver Hoxha, much of the river and its environment remain unexplored. An international team of scientists and NGOs has been compiling data on biodiversity and the river’s morphology, to use as part of a case for preserving the Vjosa. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

Dam construction site near Kalivaç. The project began in 2007 as a collaboration between Deutsche Bank and Italian businessman, Francesco Becchetti, but was stalled for several-years after charges of fraud and money-laundering were brought against Becchetti. He has denied these charges. The Albanian government nulled the contract and a new one was awarded to Turkish Ayen energy, who also hold the contract for the Poçem dam. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

Fields between Kalivaç and Kuta, which would be lost to flooding for the reservoir created by the Poçem dam. Electricity generation could come to a standstill within 30 years due to sediment built-up in the reservoir. This would require expensive and invasive dredging equipment to be brought into the area in order to clean debris. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

In “The Lament of the Mountains” photography series, Nick St.Oegger looks at ‘malësorët’of Kelmendi, a true pastoralist shepherd culture, and one of the last in Europe, whose economy is threatened by a dozen of dams planned to be constructed along alpine rivers. As government receives subsidies and loans from Western banks to solve the energy crisis with the construction of small scale hydropower plants, there is no public consultation for evaluating how it will affect the rich biodiversity and the lifestyle of highland shepherds. In Italy, Austria and Greece, UNESCO has recognized for protection the practice of pastoral shepherds, but there is no such status in Albania, which make their existence even more difficult.

Koprisht, Kelmend Region, Albania. Historically one of the most isolated regions in the country, most of Albania’s Northern mountains were never fully conquered during the Ottoman Empire’s 500year reign. The highland ‘malësorët’people have fiercely defended the region for centuries, operating under a strong system of tribal alliances. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

Gazmend Bikaj collects brush from the surrounding forests to construct a roof over a livestock enclosure in Koprisht, Kelmend region, Albania. Gazmend is a shepherd from Kalsa, a hamlet some 30km away, where he lives with his family most of the year. During the summer months they migrate to an encampment in the high pastures of Koprisht, taking a flock of sheep that belong to a farmer from the lowlands. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

During the summer, shepherds live in the high mountains in a temporary shelter called a ‘stan’. The structures are basic with an exposed dirt floor, stove and loft area for sleeping. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

Fonsi Bikaj moves a herd of sheep along the road from Tamarë to Koprisht, 35km away. Earlier in the day his father Gazmend had taken the sheep from their owner in the lowlands outside the city of Shkoder and walked with them into Kelmend. This process of transhumance has been practiced in the mountains for hundreds of years and risks dying out due to a decreasing population as well as threats from climate change and hydropower development. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

The site of a small scale hydropower plant in between the villages of Tamarë and Selcë, Kelmendi region, Albania. Small scale hydropower dams involve construction of several kilometers of pipeline that would divert the river underground, potentially drying out large sections of it and affecting the delicate biodiversity in the area. There are also concerns about the effect this would have on the local endangered trout population, which migrate along the river. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

A completed section of pipeline for a small scale hydropower plant near the village of Selcë, Kelmend region, Northern Albania. River water will be diverted into these pipelines to generate electricity at a power station downstream. Locals worry about the effects this will have on their access to water, which is critical for agriculture and raising livestock. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

Cousins Gjyste and Age Murçaj, in the village of Vukël, Kelmendi region, Albania. Emigration from the region has left a mainly ageing population, who often rely on family members living abroad for financial support. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

Anjeza Bikaj shakes out a tablecloth near the family’s summer encampment, Kelmendi region, Albania. Anjeza and her siblings take turns helping with household chores, milking the sheep and taking them into the surrounding mountains to graze. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

Albana Bikaj shares a moment of laughter with her sister Anjeza as the two make homemade playing cards at the family’s summer shelter in Koprisht, Kelmend region, Albania. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

Wilson Bikaj, one of Gazmend’s sons, help round up sheep in an enclosure in Koprisht, Kelmend region, Albania. The entire Bikaj family takes part in the process of caring for and grazing the sheep during the summer months. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

Rest near a café on the banks of the Cemi river, near Kozhnje. The region has seen an exodus of young people in recent years, with some 60% of the population of Kelmend emigrating, many to the United States. Job opportunities are limited and poverty levels remain high in the region, which has seen little development since the fall of the communist regime. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

High pastures above the treeline near Lepushë, where several shepherds have their summer encampments. Historically the Albanian Alps have also been known as Bjeshkët e Nëmuna (the Accursed Mountains), owing to their isolation and difficult terrain. This has left the area largely untouched until recent plans to construct hydropower dams on several of the region’s rivers. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

Henri Cartier-Bresson

Henri Cartier-Bresson is a French photographer, one of the most influential figures of the 20th century. He is considered the pioneer of candid street photography, the father of modern photojournalism, who created a new practice and aesthetic in photography, making photojournalism accepted as an art form. His name is associated with the Leica 35mm film camera and the concept of "decisive moment".

Henri Cartier-Bresson

(France 1908-2003)

Portrait Henri Cartier-Bresson with his camera Leica M3, © Jane Bown, Paris 1957

Henri Cartier-Bresson is a French photographer, one of the most influential figures of the 20th century. He is considered the pioneer of candid street photography, the father of modern photojournalism, who created a new practice and aesthetic in photography, making photojournalism accepted as an art form. His name is associated with the Leica 35mm film camera and the concept of "decisive moment". Nowadays where we are surrounded by a sea of images, when we shoot digitally and download thousands of photographs in social media, the legacy of Henry Cartier-Bresson not only isn’t outdated, but radher it teaches us about the ethics and technique of photography. Henri Cartier-Bresson was considered “a responsible artist, responsible to his craft and to his society” (L.K)

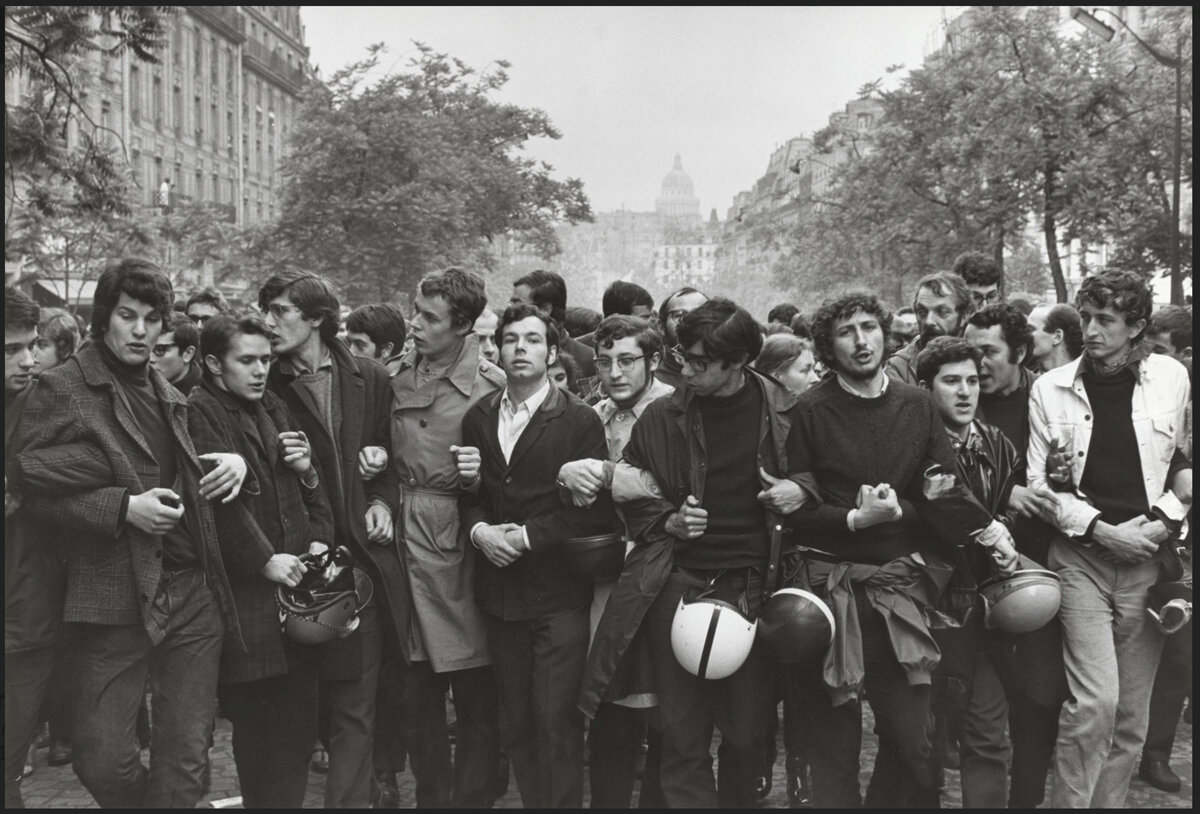

He is the avant-garde artist, the young rebel, the wildlife hunter in Africa, the former prisoner in Nazi camps, the photojournalist of the main events after the World War II, the co-founder of Magnum photo agency, a figure who revolutionized the photographic image. And yet he remained a silent figure, preferring to stay anonymous and not to give interviews. He was the person who stood behind the camera waiting for the perfect moment to appair, who carefully craft the shot, and preferred to immerse in the environment he was going to photograph. In the student revolts in Paris in 1968, despite the turbulent events, witnesses say that Bresson shot at a rate of 4 photos per hour. As he says 'I'm not interested in photography, I am interested in people'. For nearly half a century he photographed the major events of 20th century; the Spanish Civil War, the end of World War II, Gandhi a few minutes before his assassination in 1948, the first days of the communist regime in China in 1949, Indonesia emerging from colonialism, etc. He was the first Western photographer to be allowed to photograph in Soviet Union during the Cold War. Bresson's merit is that he created beautiful and poetic images, which portray the importance of place and time. As he says: "My goal was to express the essence of a phenomenon in a single image" which synthesizes his idea of decisive moment

© Henri Cartier-Bresson, Heeres, France 1932

© Henri Cartier-Bresson, Behind the Gare St.Lazare, Paris France, 1932

© Henri Cartier-Bresson, “Inside the sliding doors of the bullfight arena” Valencia Spain, 1933

Beginnings in Photography

Henri Cartier-Bresson started photography in 1931, when he bought the new Leica 35mm film camera, that accompanied him for nearly half a century. He belongs to the first generation of European photographers who explored the creative potential of small handheld camera. For Bresson - "Photography is an instant drawing, and the secret is to forget you are carrying a camera." His initial desire was to become a painter, (after refusing the family's request to continue the tradition of the family textile business). The main influences in his visual formation, which were expressed later in his photography, were the formal geometry of Renaissance painting and the serendipity of Surrealism, together with a strong adventure spirit. Influenced by the school of the cubist painter Lohte, Henry developed an interest in classical painting with strict mathematical proportions. He later said that everything he knew about photography he had learned from Lohte. For Bresson, the search for geometric order in the composition in viewfinder was an immense joy and a main criteria in his photographic process. He never croped the photos but insisted that they be presented as he had shot them, even with the black frame of the negative development. "You shoot properly while it's there", thus reinforcing the idea that the photo should be shot properly in the moment of its composition in the viewfinder. In this way Henri Cartier-Bresson helped the credibility of the photojournalism, untouched by editing.

© Henri Cartier-Bresson, “Two children in the narrow sunlight streets” Seville Spain, 1933

© Henri Cartier-Bresson, A group of people in front of a wall filled with small windows, Madrid Spain, 1933

The second influence in Bresson's photography comes from a less rational movement such as Surrealism, with which he came in contact in his youth during meetings with the leading figures of the movement at "Cafe de la Place Blanche" in Paris. From Surrealism he adopted the philosophy of spontaneous, chance and intuition. " For me the camera is a sketch book, an instrument of intuition and spontaneity, instant master, which in visual terms, asks and decides simultaneously" For Henri Cartier-Bresson, the Leica 35mm film camera with 50 mm lens, was the most appropriate instrument to express his artistic creativity. While Bresson was looking for the spontaneous, his compositions are not the product of serendipity, but he carefully chooses the stage and wait until all the elements appear in the viewfinder, so to fix in the film the decisive moment.

@ Henri Cartier-Bresson, “A group of children play amongst rubble” Seville Spain, 1933

© Henri Cartier-Bresson, “Sunday on the banks of River Seine” France 1938

Although his photographs reflect an event or historical moment, they are independent artistic entities. Seeking beauty in ordinary things, he associated art with photojournalism. His first photographs belong to the period 1932-1935 during his travels to Italy, Spain, Morocco, Mexico, which were presented in several photographic exhibitions. The photographs of this period are considered to be the best of Bresson and the history of modern photography inspired by Surrealism.

© Henri Cartier-Bresson, Coronation of King George VI, London England, 12 May 1937.

Bresson in cinematography

During his stay in New York in 1935, Bresson met Paul Strand who encouraged him to pursue cinematography. Between 1936 and 1939 he worked as an assistant of French director Jean Renoir in the production of Une Partie de Campagne (A Day in the Country) and La Règle du Jeu (The Rules of the Game). In 1937 Bresson produced the first documentary on medical aid in the Spanish Civil War entitled Return to Life. Although Bresson did not belong to any political party, his anti-fascist orientation led him to work for the left-wing newspaper Ce Soir where he met other photojournalists with similar interests, such as Robert Capa and David "Chim" Seymour, with whom he founded after war the Magnum photo agency. With the start of World War II in 1939, Bresson joined the Army unit for film and photography. In 1940 he was captured by the Germans and imprisoned in forced labor camps. After two unsuccessful escape attempts, he managed to escape a third time, after which time he worked illegally. After the war, Bresson returned to cinematography with the direction of the film La Retour, on the return of war displaced persons. Bresson returns to cinematography in the late ’60s with Impressions of California (1969) and Southern Exposures (1971). As he states, Bresson quit making films because he was not attracted to the direction of actors and the lack of spontaneity. But from the cinematography he learned the narrative and the expressive moment. Bresson is credited with influencing the development of the cinema verite genre.

© Henri Cartier-Bresson, “Downtown Manhattan NewYork” USA 1947

Bresson in Magnum

After Bresson's exhibition at MOMA New York in 1946 and his trip to America which concludes with a photo book, Bresson undertakes to pursue the profession of photojournalist following the advice of Robert Capas, who understood the importance of this profession in post-war society. Together with Robert Capa, David Seymour, George Rodger, he founded in 1947 the first cooperative photography agency Magnum. The organization provided the newspapers and magazines the coverage of major events by the most talented photojournalists, preserving the author rights and freedom of choice. Under the aegis of Magnum, Bresson photographed major events in India, China, Indonesia, Egypt. These photographs were published in the form of several books between 1952 and 1956. The best known of these is the one published in 1952 entitled "Images à la sauvette", translated into English "The decisive moment", which refers to Bresson's main idea on photography – “the elusive instant when, with brilliant clarity, the appearance of the subject reveals in its essence the significance of the event of which it is a part, the most telling organization of forms”.

© Henri Cartier-Bresson, “Refugees exercising in the camp to drive away lethargy and despair” Punjab India, 1947

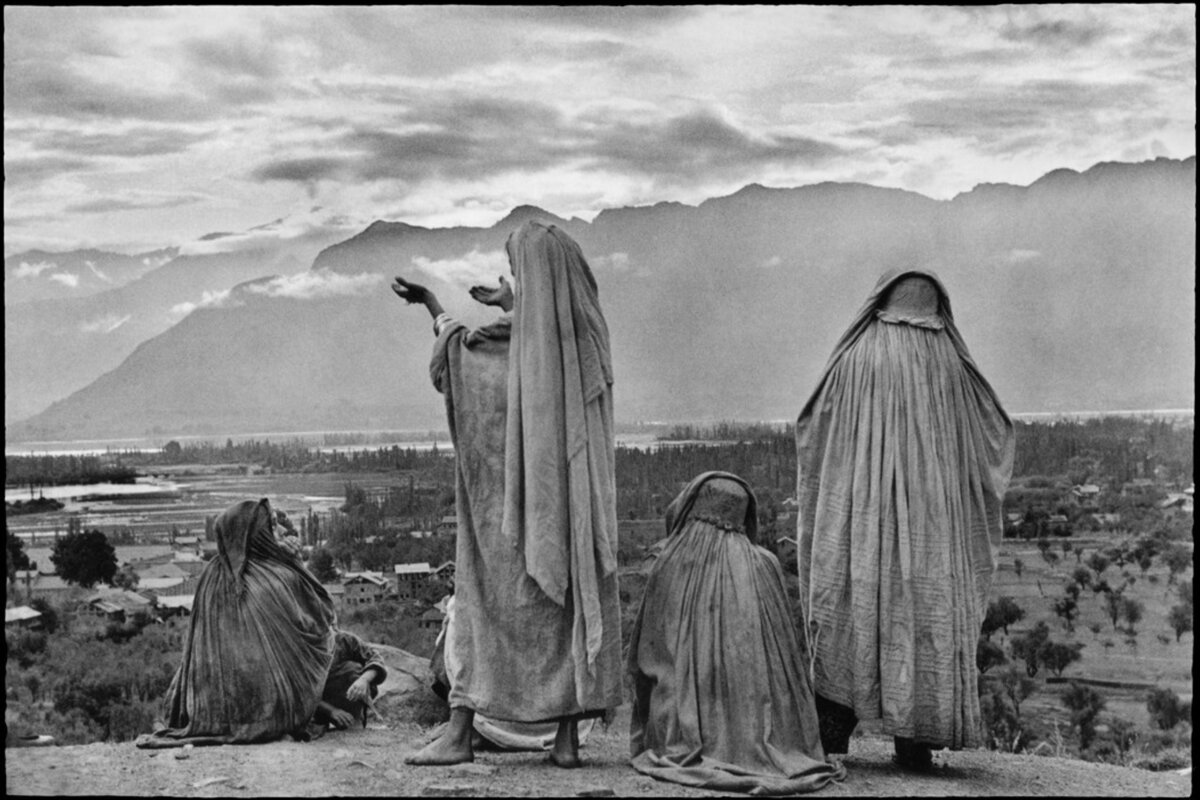

© Henri Cartier-Bresson, “Muslim women praying toward the sun rising behind the Himalayas” Kashmir India, 1948

© Henri Cartier-Bresson, Crowds reaching into the train carrying Gandhi’s ashes hoping to pay the last tribute to their leader Delhi India 1948

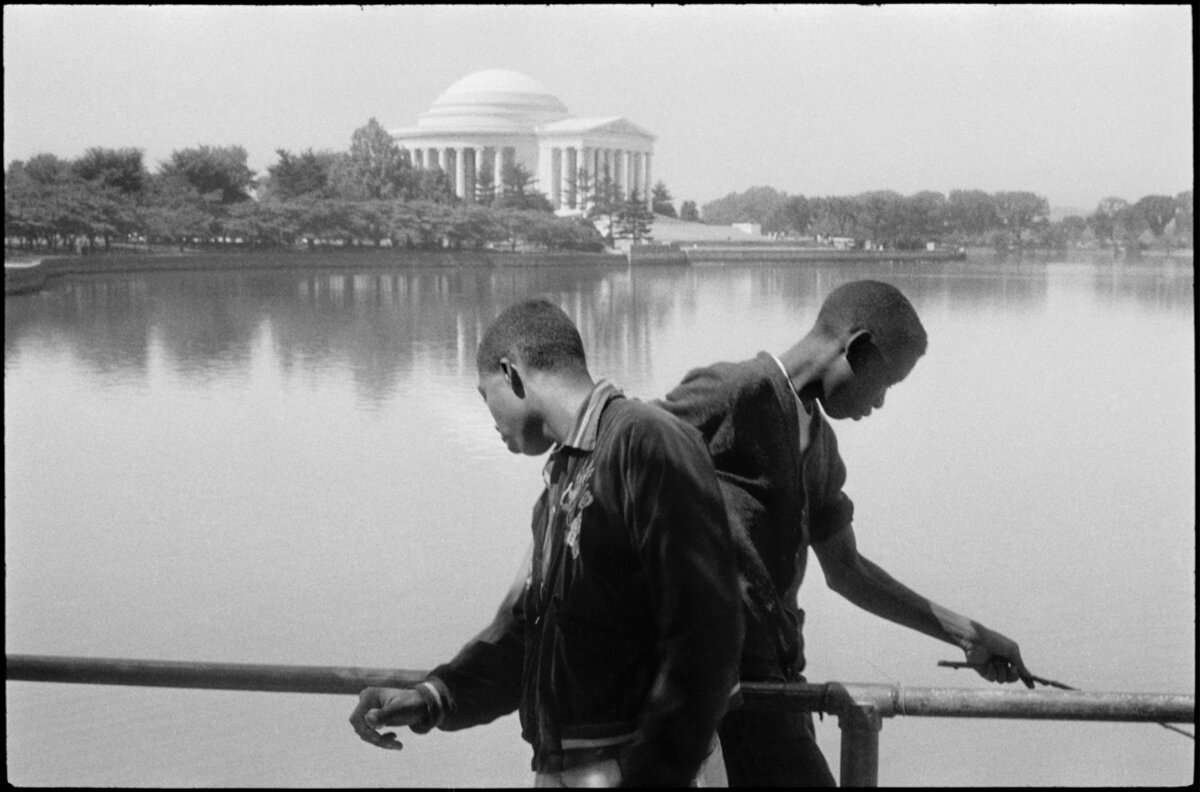

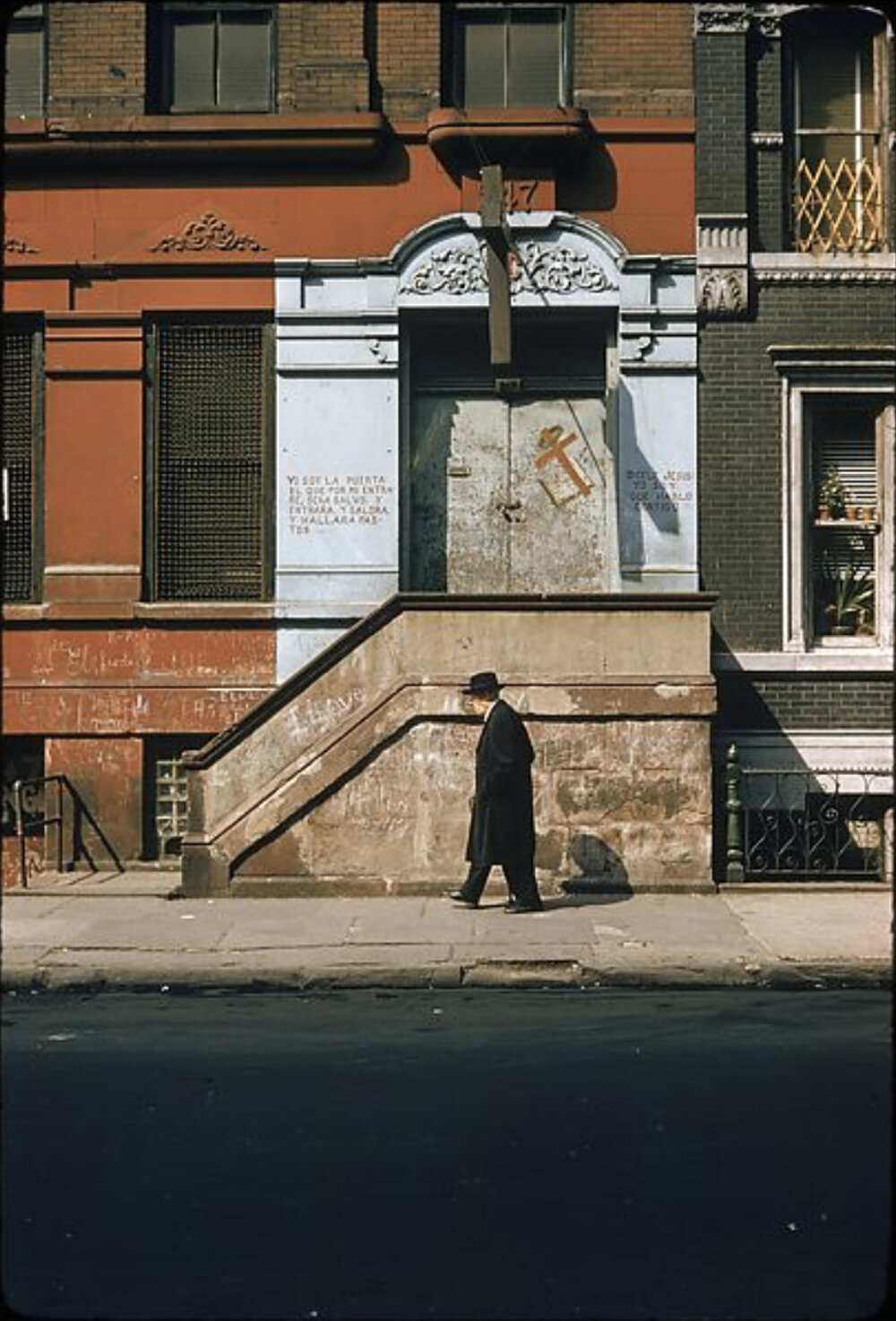

© Henri Cartier-Bresson, Washington DC, USA, 1957.

© Henri Cartier-Bresson, “Sale of gold in the Last Days of Koumintang, Shangai” China 1949

© Henri Cartier-Bresson, “Elementary School, Moscow USSR” 1954

© Henri Cartier-Bresson, Scanno Abruzzo, Italy 1951

© Henri Cartier-Bresson, Rue Mouffetard, Paris 1954

Between 1963-1965 Bresson photographed in Cuba, Mexico, India. His later books are France (1971), The Face of Asia (1972), About Russia (1974). With his nomadic spirit he witnessed after World War II the major events as the transition of powers. He photographed ordinary people with the same importance that he photographed famous figures of art and politics.

© Henri Cartier-Bresson, Cyclades Greece 1961

© Henri Cartier-Bresson, Berlin 1963

© Henri Cartier-Bresson, Berlin Wall, 1963

© Henri Cartier-Bresson, Prizren 1965

© Henri Cartier-Bresson. Ahmadabad India, 1966

© Henri Cartier-Bresson, “Funeral Ritual, Tokyo Japan” 1965

© Henri Cartier-Bresson, Brie France, 1968

© Henri Cartier-Bresson, “Simiane la Rotonde” France 1969

© Henri Cartier-Bresson, Student Demostration, Paris, June 1968.

In the early ‘70s, Bresson left photography and dedicated himself to painting. In 2003, Bresson co-founded the Henri Cartier-Bresson Foundation with his wife Martin Franck, a Magnum photographer, and their daughter. The Bresson negatives are owned by the Foundation and agency Magnum. He left a legacy of nearly half a million negatives, shot over a period of 70 years.

Links:

Magnum Agency

https://www.magnumphotos.com/photographer/henri-cartier-bresson/

Foundation Henri Cartier-Bresson

https://www.henricartierbresson.org/en/hcb/

Selected Books by Henri Cartier-Bresson

Walker Evans

Walker Evans is the American photographer who has influenced more than any other the modern documentary photography of the 20th century. With his anti-conformist nature, he rejected the prevailing pictorialist view of artistic photography, supported by the main proponent Alfred Stieglitz, and constructed a new artistic strategy based on the description of common facts in a detailed and poetic manner. Evans has been described as the photographer with the sensibility of a poet and the precision of a surgeon…

Walker Evans

(USA 1903-1975)

Walker Evans, selfportrait 1930

Walker Evans is the American photographer who has influenced more than any other the modern documentary photography of the 20th century. With his anti-conformist nature, he rejected the prevailing pictorialist view of artistic photography, supported by the main proponent Alfred Stieglitz, and constructed a new artistic strategy based on the description of common facts in a detailed and poetic manner. Evans has been described as the photographer with the sensibility of a poet and the precision of a surgeon… Following independently his artistic strategy, he built a body of work based on the description of American everyday life. His preferred subjects are the vernacular architecture, street scenes, advertising, billboards, shop windows, passers-by, automobile culture, and most important the description of American poor conditions during Great Depression. Evans is the first photographer that the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) New York dedicated a personal photography exhibition in 1938. He was an independent and authoritative figure in photography. For two decades he worked as an editor and writer for Time and Fortune magazines, where he designed the layout and the accompanied words of his photography. In the end of his career he taught photography at Yale University. His photography has influenced a generation of photographers, such as Robert Frank, Le Friedlander, Garry Winogrand, Diane Arbus, the Bechers, and other genres of art, such as: cinematography, theater, and literature.

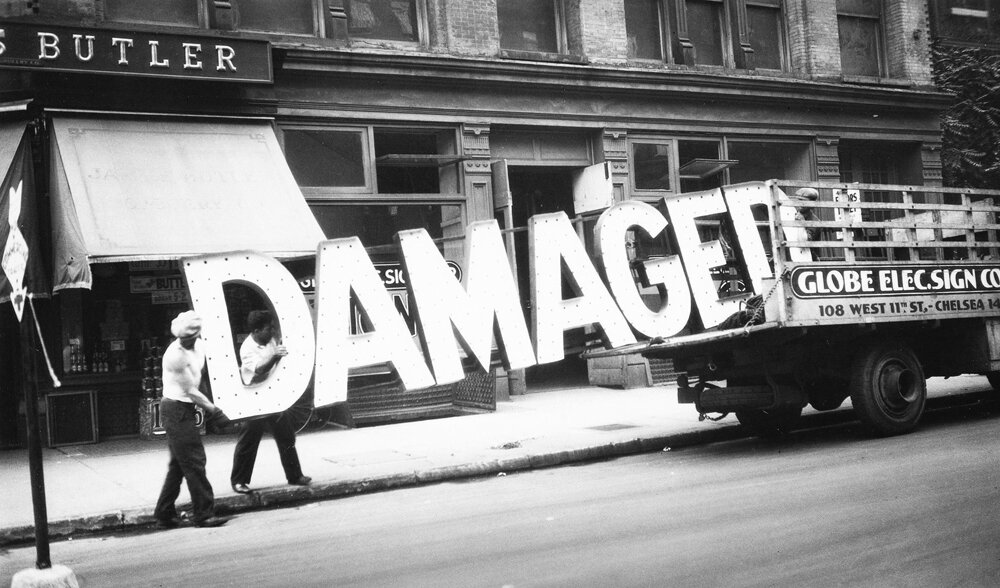

© Walker Evans, Truck and Sign New York, 1930

The first years

Walker Evans began photographing at the age of 25, with his Kodak handheld camera, during his stay in Paris, where he was studying French literature at the Sorbonne University. Evans aspired to become a writer, but upon his return to New York in 1928, he exchanged the writer's dream for the profession of the photographer. The first photographs are scenes of everyday American life and urban environments: New York streets, Victorian buildings, Brooklyn Bridge, abstract compositions of emerging new architecture, street advertisements, and storefronts. Repeating motifs in his photography are: letters, signs, numbers in billboards and road advertisements. He documented the city through the eyes of a historian and anthropologist, finding what was authentic and American in character. The main influences in his photography were: Eugene Atget and August Sander; while the favourite writer: Gustave Flaubert, from whom he adopted the saying: "An artist must be in his work like God in Creation, he should be everywhere felt, but nowhere seen”.

© Walker Evans, Brooklyn Bridge New York, 1929

© Walker Evans, U.S. Rubber Sign, New-York, 1928-1929

© Walker Evans, Movie Poster, New York, 1930

© Walker Evans, Parked Car, Small Town Main Street, 1932

© Walker Evans, Street Scene with Telephone Pole and Lines, Provincetown Massachusetts, 1931

© Walker Evans, Chrysler Building, 1930

© Walker Evans, Construction Shack, New York, 1929

Havana

In the early 1930s, Evans was sent to Cuba to photograph the worker’s conditions during the dictatorship of Gerardo Machado. Here he photographed the slums, the street beggars, the police, the port workers, developing the human side of his latter photography. The photographs were published in 1933 in the book “Crimes of Cuba”.During his stay, Evans accompanied Ernest Hemingway, to whom he left 46 photographic prints for fear of being confiscated by the Cuban authorities. These prints were found in Havana in 2002, and were presented in a photographic exhibition.

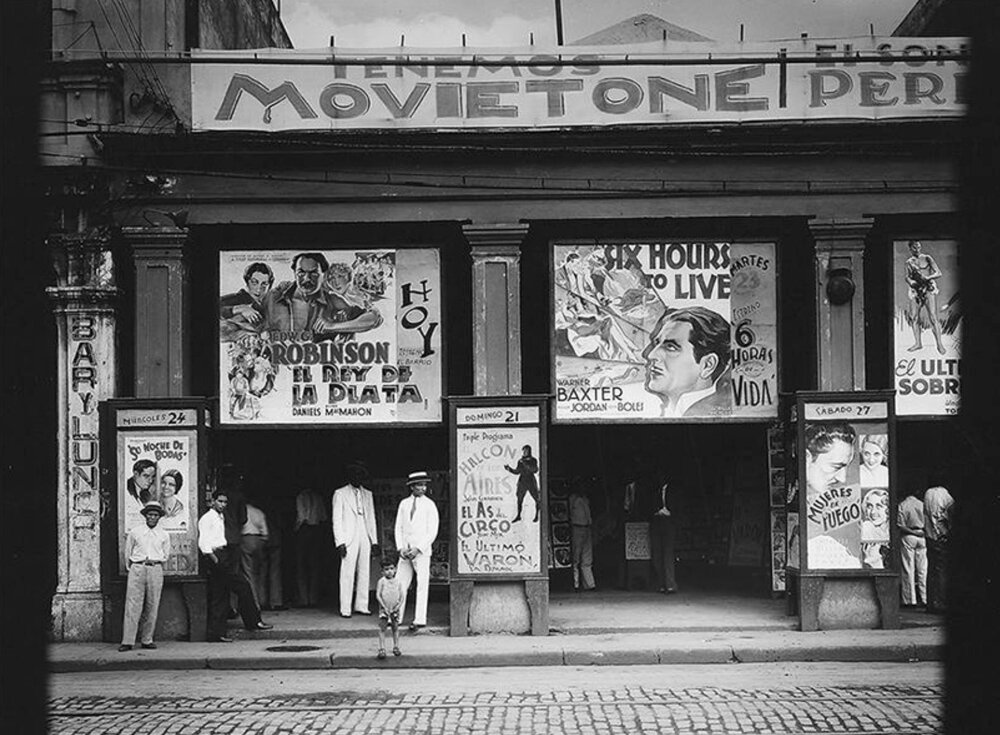

© Walker Evans, Cinema Havana, 1933

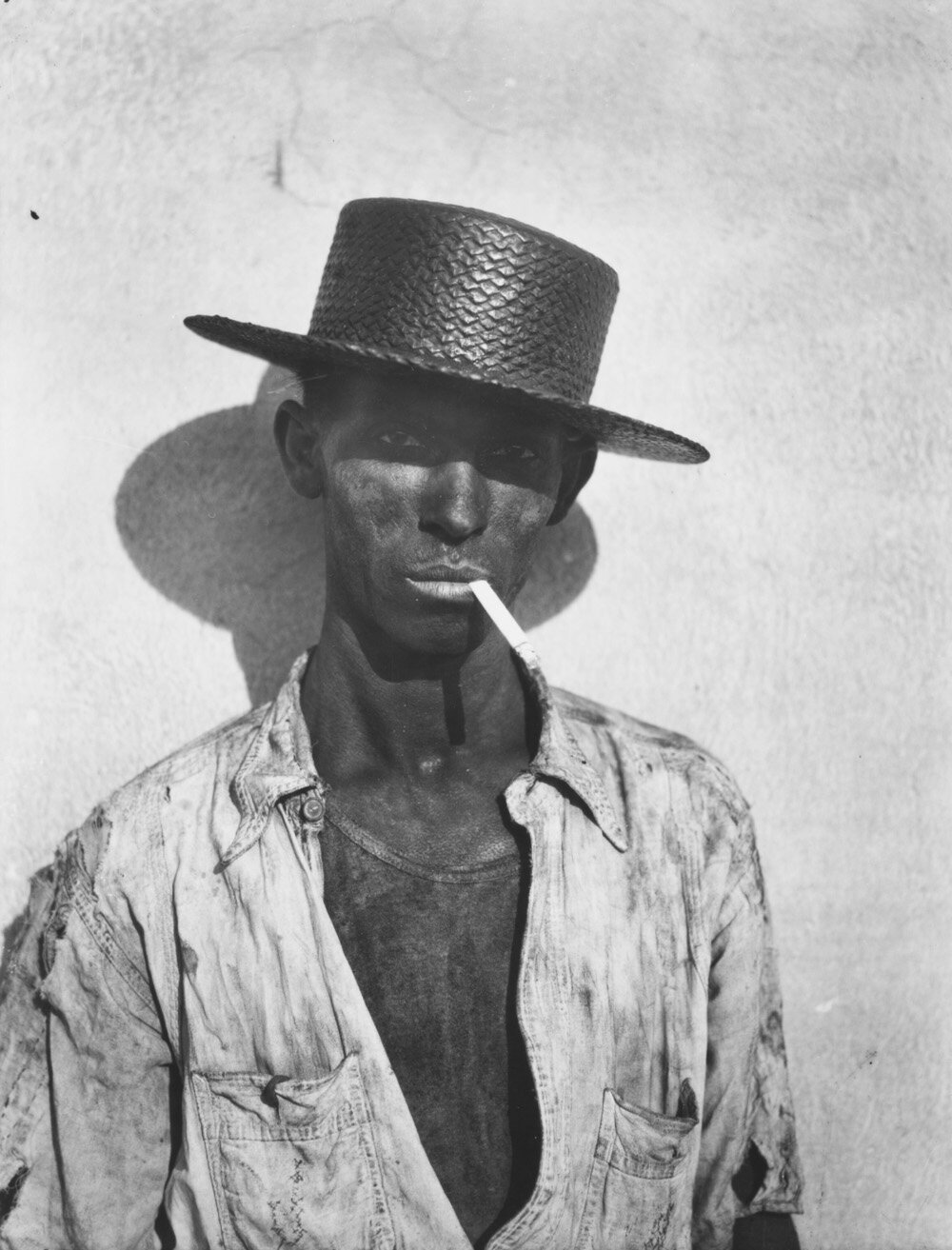

© Walker Evans, Havana Dock Worker, 1932-1933

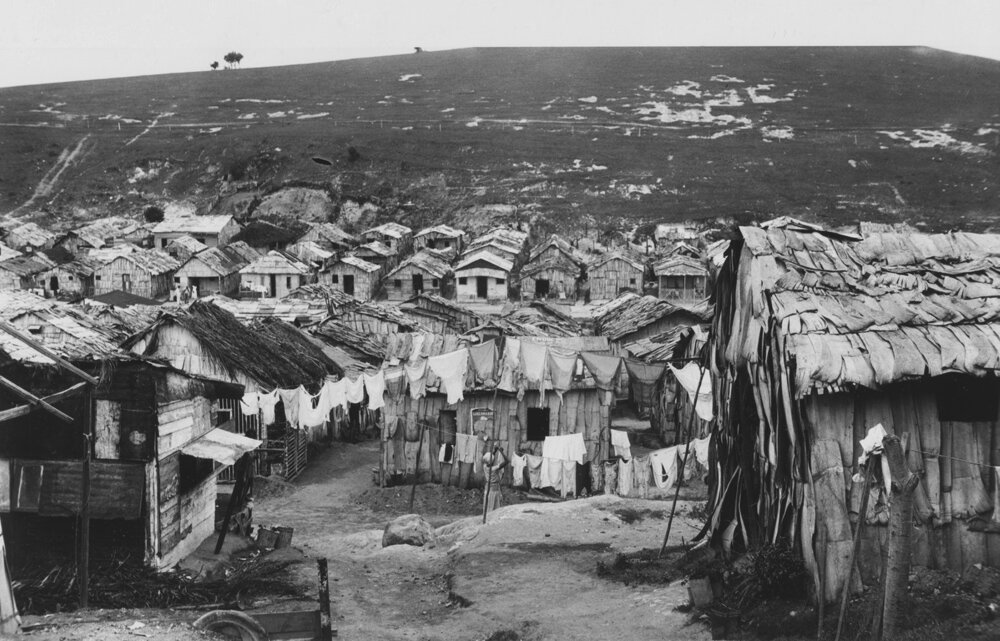

© Walker Evans, Squatters Village Cuba, 1933

Years of the Great Depression

During the years 1935-1937 Evans worked for the government's New Deal Resettlement program (later called the Farm Security), to document the life of South American farmers during the Great Depression. In this project he developed his artistic style to documented the facts in a detailed precise and neutral way, using a large format 8x10 inch camera. A collection of his works was displayed at the Museum of Modern Art in 1938 entitled "American Photographs", which is the first personal exhibition that MOMA dedicated to a single photographer. The book of the same title with 100 photographs by Evans, accompanied with a critical essay by Lincoln Kirstein, remains today one of the most influential books in the history of modern photography.

© Walker Evans, Roadside Store between Tuscaloasa and Greensboro, Alabama-1935

© Walker Evans, Easton Pennsylvania, 1935

© Walker Evans, Breakfast Room at Belle Grove Plantation White-Chapel, Louisiana, 1935

© Walker Evans, Houses and Billboards Atlanta, 1936

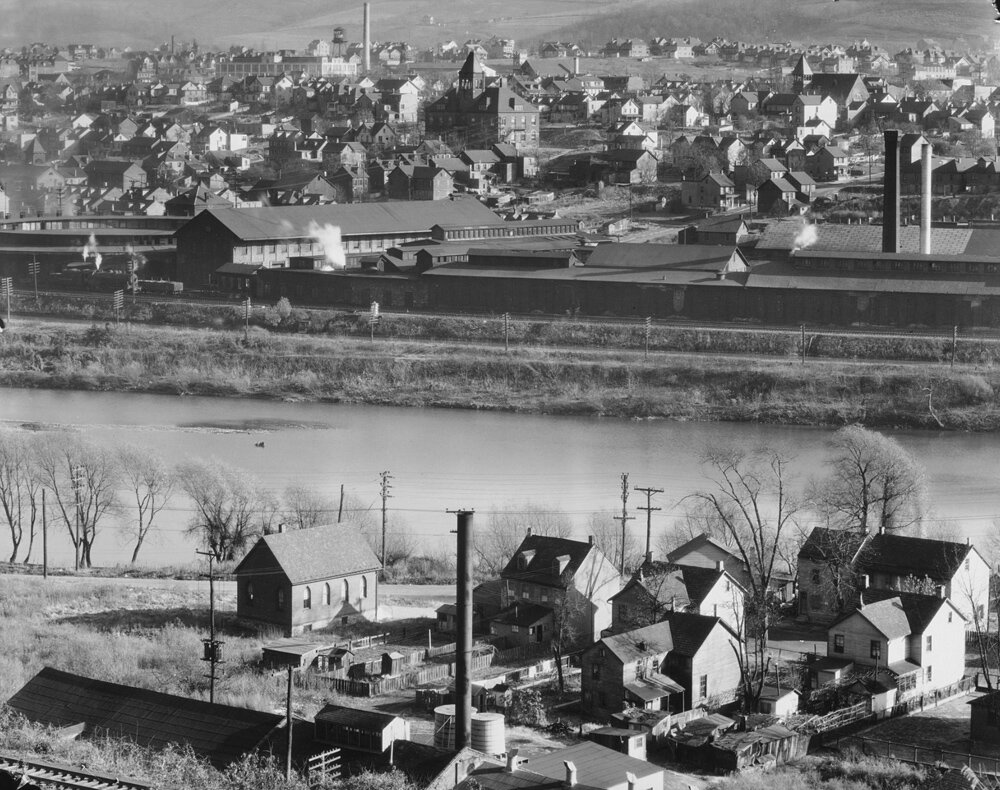

© Walker Evans, View of Easton Pennsylvania, 1936

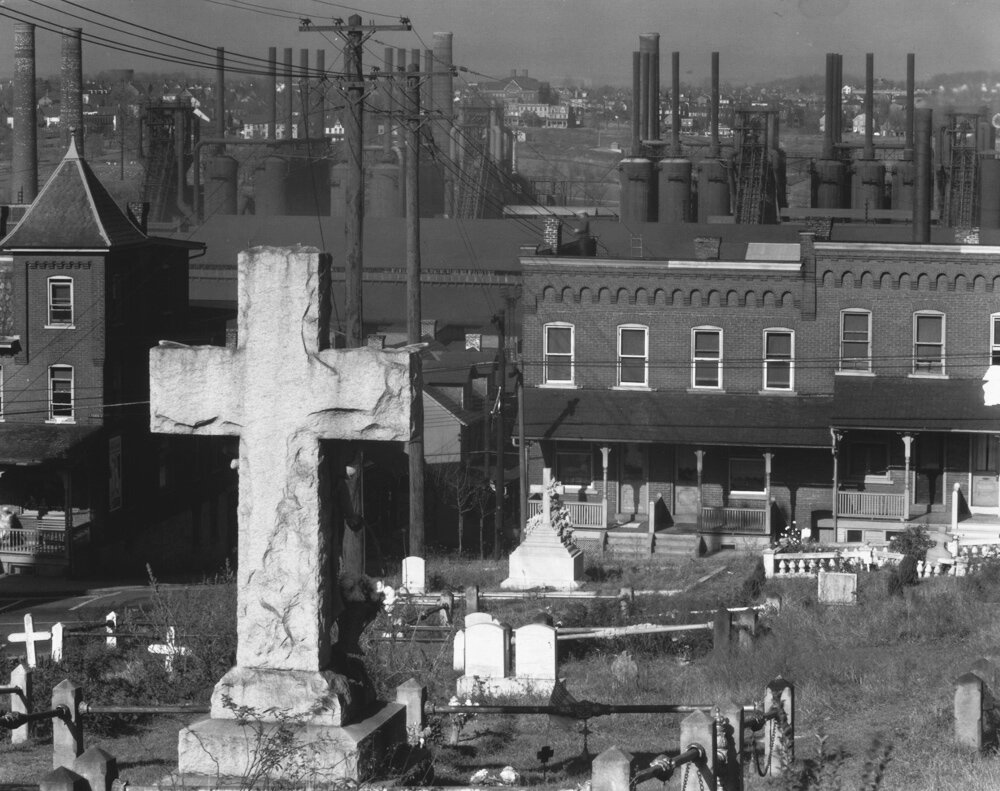

© Walker Evans, Graveyard and Steel Mill Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, 1935

© Walker Evans, Birmingham Steel Mill and Workers Houses, 1936

Let Us Now Praise Famous Men

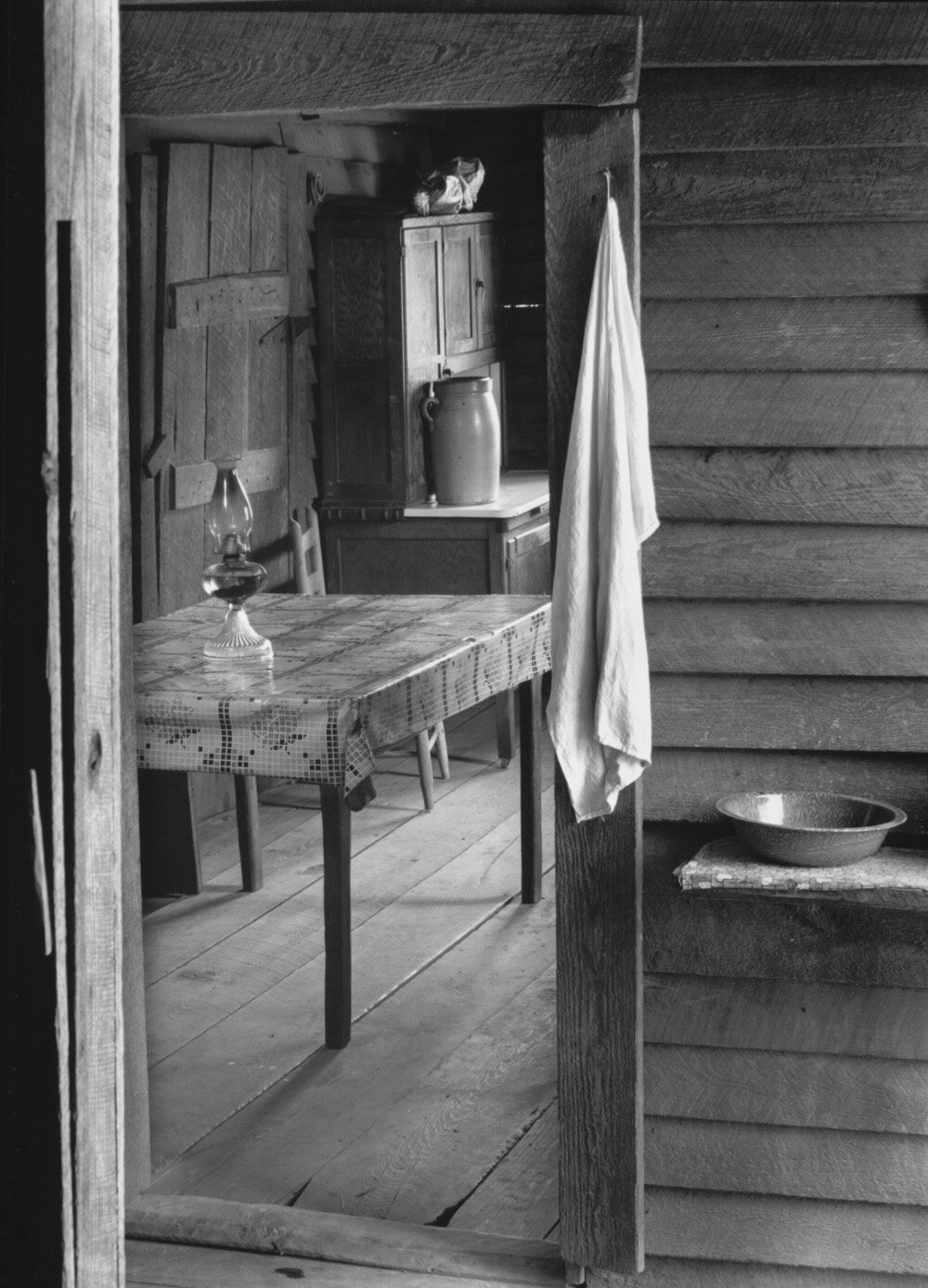

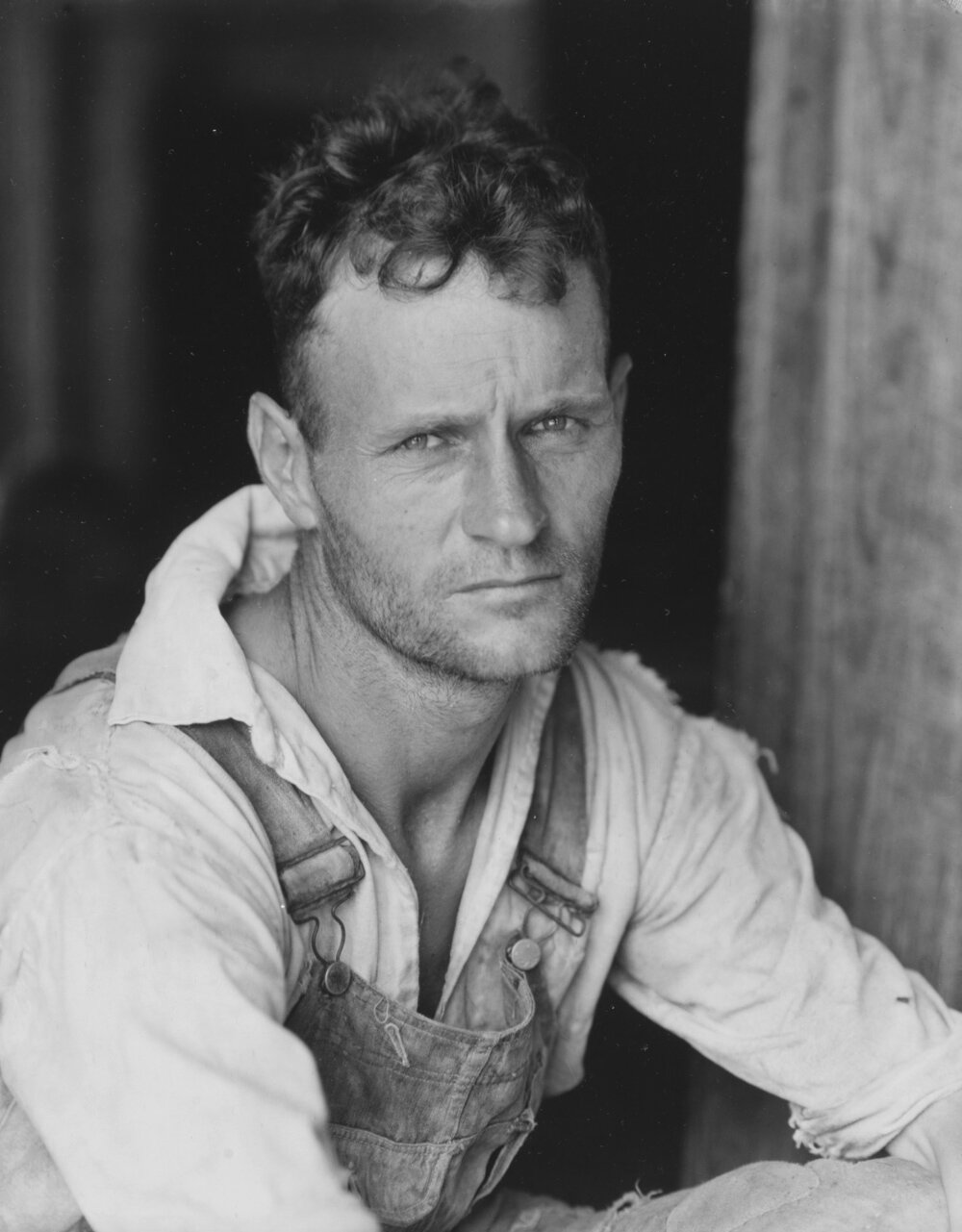

During 1936, Evans undertook a trip to the South, with the writer and friend James Agee, to document the difficult lives of three sharecropper families affected by the economic crisis. The project, which was rejected for publication by Fortune magazine, was published in 1941 in the form of a book of pictures by Evans and text by Agee, entitled "Let Us Now Praise Famous Men". The photos of this project remain iconic images of America affected by the Great Depression.

© Walker Evans, Coal Miner's House West-Virginia, 1936

© Walker Evans, Farmers Kitchen Hale-County Alabama, 1936

© Walker Evans, Sharecropper Hale-County Alabama, 1936

© Walker Evans, Church Organ and Pews, Alabama, 1936

© Walker Evans, Negro Church South Carolina, 1936

© Walker Evans, Barber Shop Vicksburg Mississippi, 1936

© Walker Evans, Country Store and Gas Station, Alabama, 1936

© Walker Evans, Roadside View Alabama Coal Area Company Town, 1936

© Walker Evans, Roadside Stand near Birmingham, Alabama, 1936

© Walker Evans, Window Display Bethlehem Pennsylvania, 1935

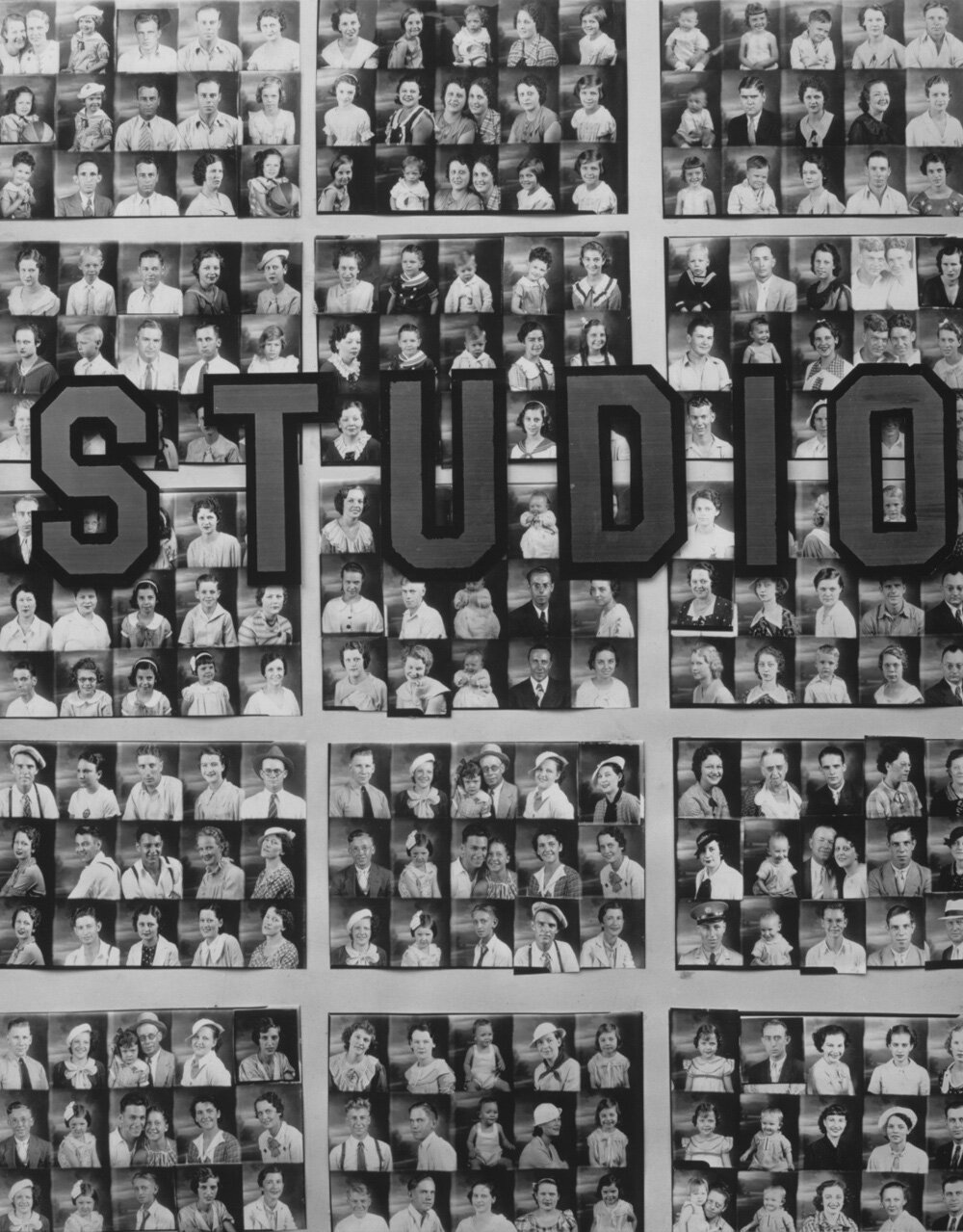

© Walker Evans, Penny Picture Display, Savannah 1936

Subway Portraits

From 1938-1941, Walker Evans photographed New Yorkers on the subway, captured by his Contax 35mm camera, hidden under his coat. The photographic series was published many years later (1966), under the title "Many are called".As he puts it, he wanted to photograph people "when the guard is down and the mask is off." The motif of casual passers-by, is a recurring motif in Evans work. While working for Fortune in 1946, he photographed with Rolleiflex a series of portraits of workers on the streets of Chicago, which are published in 2 pages of the magazine under the title "Labor Anonymous".

© Walker Evans, Subway Portrait, 1938-1941

© Walker Evans, Subway Portrait, 1938-1941

© Walker Evans, Labor Anonymous, Fortune November 1946, pp152-153

Years in Time and Fortune Magazine

Evans worked for Time magazines (1943-1945), and later for Fortune (1945-1965) as a photo editor, producing over 400 photos and 46 articles. Evans had complete control over the publication of his photographs, he chose the subjects himself, the accompanying writings and the layout of the magazine. Having photographed America at its most difficult years, now Evans captures its rise as the world superpower, the culture of automobile and consumerism.

© Walker Evans, Burlesque Theater, Chicago 1946

© Walker Evans, Views of Pedestrians Uniontown, Maryland, 1946

© Walker Evans, Pedestrians Uniontown Maryland, 1946

© Walker Evans, Shoppers Randolph Street, Chicago 1946

© Walker Evans, Untitled Chicago, 1946

© Walker Evans, Lamp on Table, Evans Apartment New-York, 1946

© Walker Evans, Details of Clapboard House, 1960

Last years

In 1965, Evans began teaching photography at Yale University School of Art and Design. During the ’70s he experimented with colour photography, and the Polaroid SX-70 camera, with an unlimited supply of film from Kodak. These photographs are interesting studies of colour and shape, on Evans' preferred motif: architecture, portraits and signs.

© Walker Evans, New-York Streets, 1957-1959

© Walker Evans, New-York Streets, 1957-1959

© Walker Evans, Telephone Pole and Red Barn, 1974

Walker Evans's photographs are in the collections of:

Selected Books by Walker Evans

W. Eugene Smith

W. Eugene Smith was an American photographer, known as the father of photo essay in the American editorial of the '40s and '50s. He created the genre’s model and standards that were followed for a long time. Eugene Smith worked for several magazines of the time such as: Newsweek, Life, and for the agency Magnum as a freelancer.

W. Eugene Smith

(U.S.A 1918-1978)

Portrait of W. Eugene Smith. Photograph by Fran Erzen

W. Eugene Smith was an American photographer, known as the father of photo essay in the American editorial of the '40s and '50s. He created the genre’s model and standards that were followed for a long time. Eugene Smith worked for several magazines of the time such as: Newsweek, Life, and for the agency Magnum as a freelancer. His most famous photos essays are (in chronological order): World War II (1943), Country Doctor (1948), The Midwife (1951), The Spanish Village (1951), Man of Mercy (1954), Pittsburg (1955), Jazz Loft (1965), Minamata (1971).

During his career in photography, Eugene Smith is distinguished for his humanism, the need to know his subjects well, the perfectionism and anti-conformism to the dictate and boundaries set by the mass media. More than a photojournalist, he is a director of storytelling and a poet of photography through the use of light and chiaro-scuro.

US Marine World War II. Photograph by W. Eugene Smith

A Hospital in a Philippine Cathedral (Island of Leyte). Photograph by W. Eugene Smith

“The walk to Paradise garden” 1946, Photography W. Eugene Smith

“Country Doctor, Ernest Ceriani”, 1948, Photography W. Eugene Smith

His most important photo essays addressing the theme of urbanisation and consequences of industrialisation are; Pittsburg (1955) and Minamatas (1971).

Eugene Smith began photographing Pittsburgh in 1955 when writer and publisher Stefan Lorant asked him a series of photographs to illustrate his book on the city's 100th anniversary. Smith saw this commission as a personal project. He extended the duration of the project from three months to three years, and expanded the subject by photographing the modernity and the steel industry, as well as other topics that did not belong to government propaganda, such as working class conditions, poor neighbourhoods, the immigrants, the African American community, preceding the riots of the 1960s. In this project, Smith built a rich archive consisting of 17,000 photographic images and audio recordings, a small part of which have been published.

Inside Mellon National Bank. Photograph by W. Eugene Smith.

International Union of Electrical, Radio, and Machine Workers. Photograph by W. Eugene Smith

City Council Chamber, Pittsburg, © Photography W. Eugene Smith

Children at Colwell and Pride Streets, Hill District. Photograph by W. Eugene Smith

Pittsburg, 1955, Photography by W. Eugene Smith

Sixth Street Bridge over Allegheny River. Photograph by W. Eugene Smith

Steelworker wearing goggles and a hardhat. Photograph by W. Eugene Smith

Rails, Homestead works, U.S. Steel, Monongahela River. Photograph by W. Eugene Smith

US Steel Pittsburg, 1955 Photograph by W. Eugene Smith

Pittsburg 1955 Photograph by W. Eugene Smith

In Minamata series (1971-1973), Eugene Smith photographs the inhabitants of Minamata coastal area in Japan affected by a severe disease caused by mercury in the industrial waste of Chisso factory, a giant chemical industry in the area. In 1972, Smith was attacked by Chisso Company, to stop the publication of the project on Minamata disease, which caused him severe injuries and loss of vision. The photo essay was published in 1975 and its main photo was ‘Tomoko Uemura in Her Bath”, shot in 1971, showing a mother in a traditional Japanese bathtub, with her daughter deformed by the disease. The photo drew public attention to the Minamata disease. Smith's photographs were the main evidence in the trial against Chisso, and the first case in Japan where a company became liable of the damages it caused to the people, which made Smith a national hero in Japan.

Minamata, 1972 Photography W. Eugene Smith

Minamata 1971 Photograph by W. Eugene Smith

Goi, near Tokyo. Demonstration at the Chisso Plant. 1971 Photograph by W. Eugene Smith

Demonstrators against the Chisso Chemical Company demonstrating in front of the plant near Tokyo during the Pollution Board hearings. 1971. Eugene Smith

After Minimata project, Eugene Smith returned to America, but was not able to photograph anymore. He taught at university and arranged his archive until 1978, when he died of a heart attack. Eugene Smith believed in the power of photography to change the world. In 1980, the Eugene Smith Fund was established to finance humanitarian photographic projects that cannot be funded by the mass media, contributing to the growth of the independent voice of photographers.

W. Eugene Smith Fund: https://www.smithfund.org/humanistic-photography