Saul Leiter

Saul Leiter was an American painter and photographer known for his photographs of New York City in the late 1940s through the ’60s, and is considered a pioneer of color street photography. Leiter found quiet moments within the urban chaos and portrayed them pictorially. His work has connections to American Abstract Expressionism and the New York School of Photography. His photographs are distinguished by painterly colors, abstract compositions, minimalism, intimacy, and voyeurism…

Saul Leiter

(USA 1923- 2013)

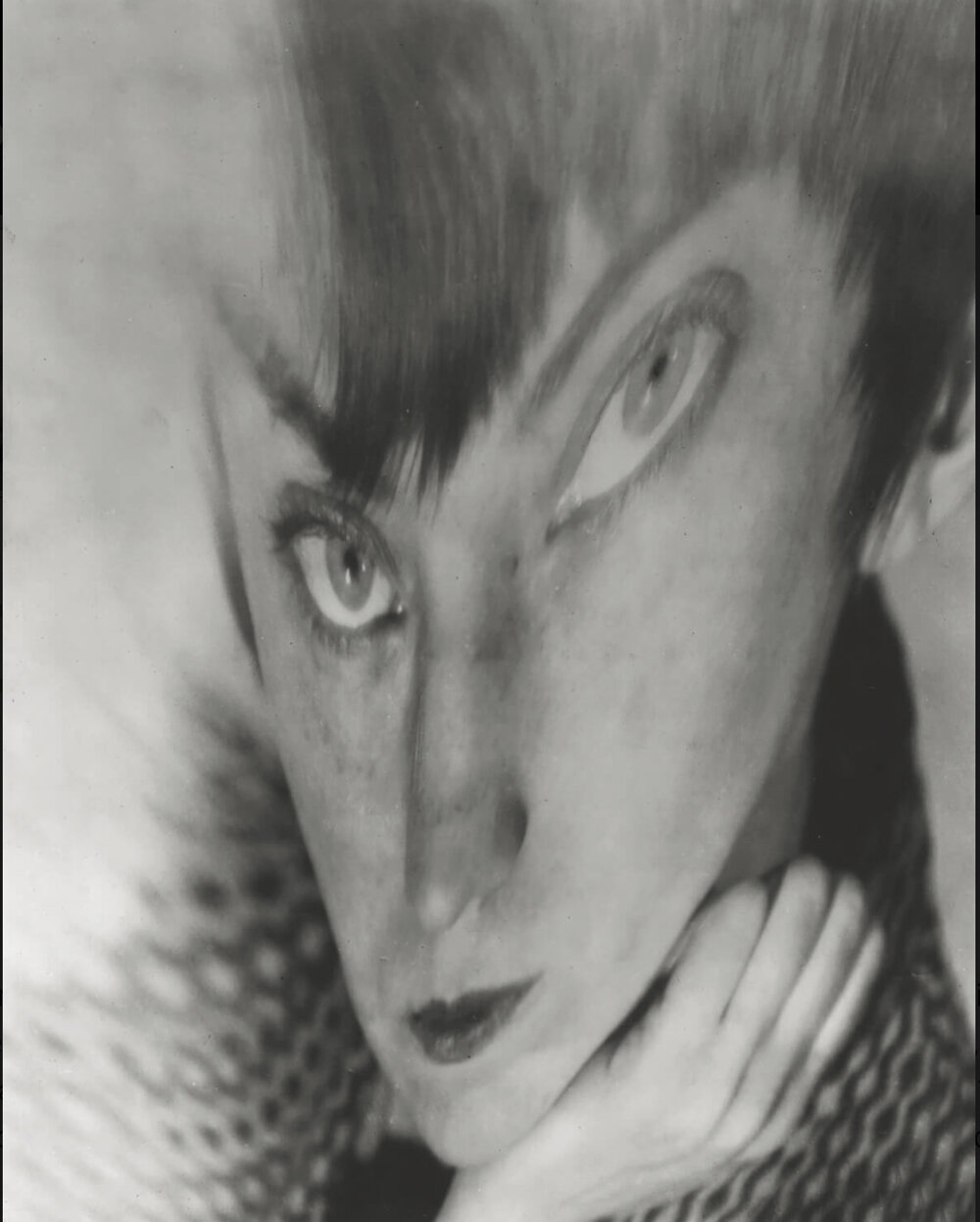

Saul Leiter, Self-Portrait 1950, credit © Saul Leiter Foundation

Saul Leiter was an American painter and photographer known for his photographs of New York City in the late 1940s through the ’60s, and is considered a pioneer of color street photography. Leiter found quiet moments within the urban chaos and portrayed them pictorially. His work has connections to American Abstract Expressionism and the New York School of Photography. His photographs are distinguished by painterly colors, abstract compositions, minimalism, intimacy, and voyeurism, which stands out from the work of his contemporaries like Robert Frank, Diane Arbus, and William Klein. “I take photographs in my neighborhood. I think mysterious things happen in familiar places.”

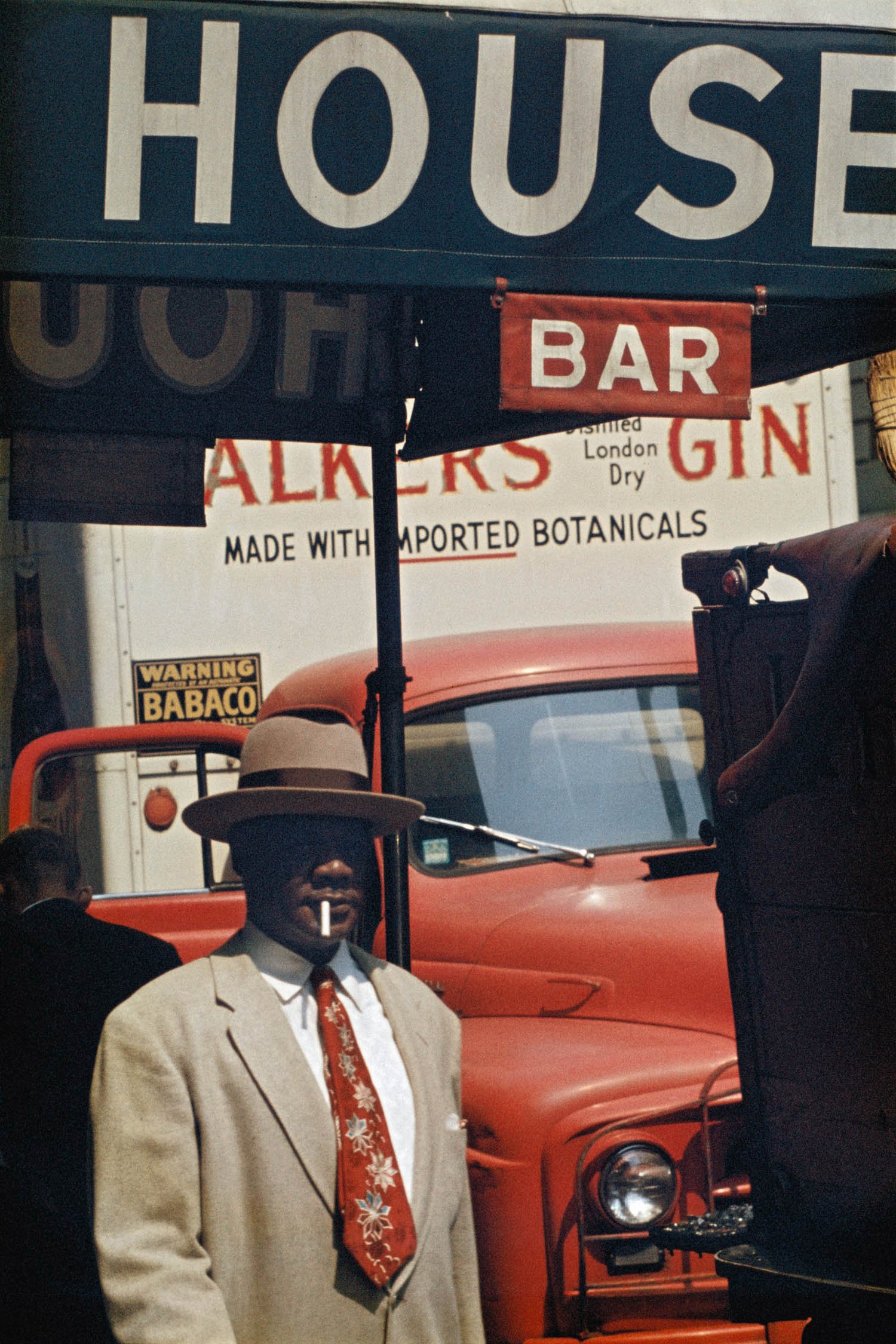

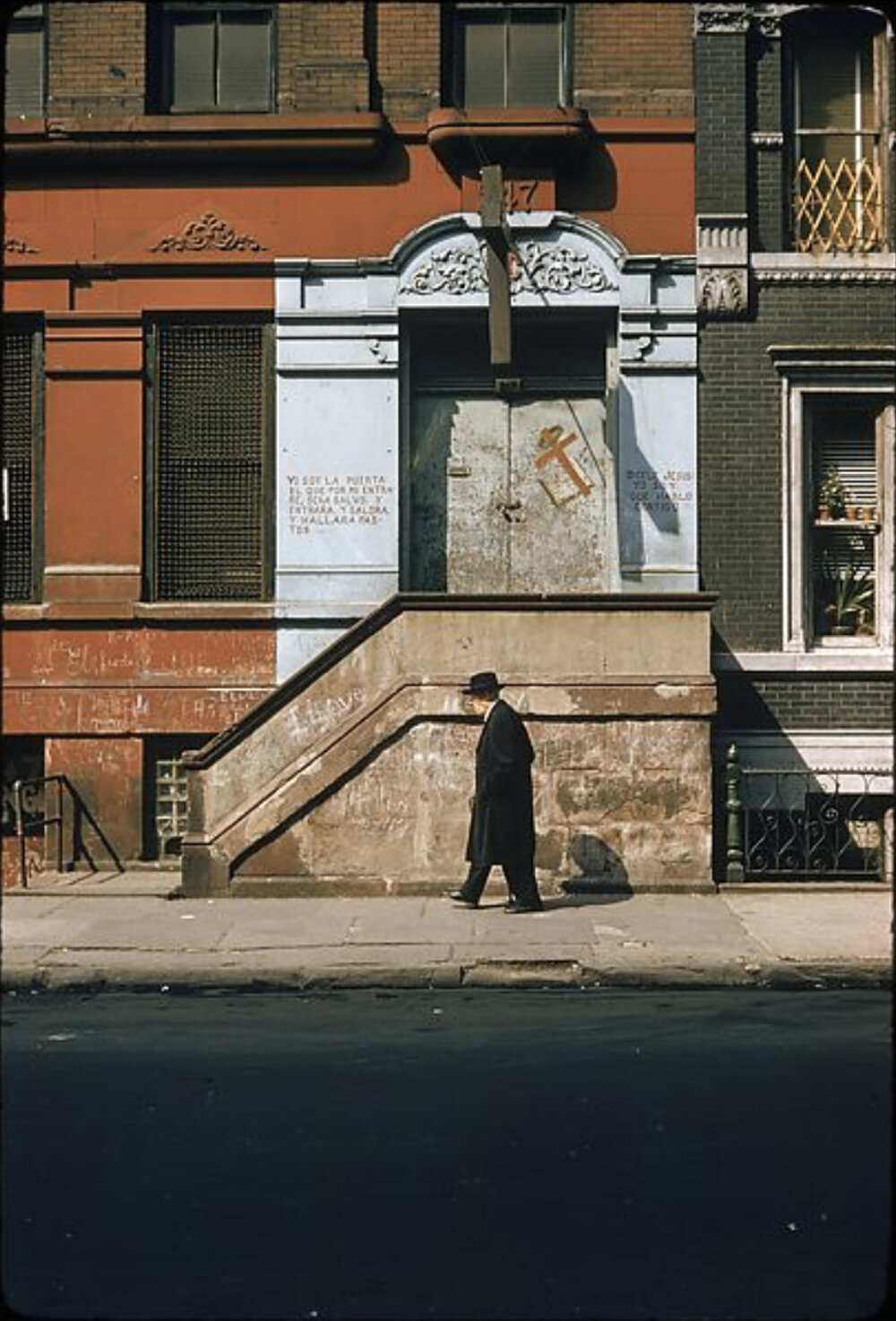

Saul Leiter, Taxi 1957, credit © Saul Leiter Foundation

Among Leiter’s favorite subjects are passers-by, or their reflections, photographed from shop windows along with umbrellas, snowy days, taxis, signs, and street advertisements, forming abstract compositions in overlapping layers of focus and out of focus. “I happen to believe in the beauty of simple things. I believe that the most uninteresting thing can be very interesting.” In the documentary movie dedicated to Leiter, by Tomas Leach, entitled In No Great Hurry: 13 Lessons in Life with Saul Leiter, at the age of 88 the photographer says, "I may be old-fashioned. But I believe there is such a thing as a search for beauty - a delight in the nice things in the world. And I don’t think one should have to apologize for it.”

Saul Leiter, Red Curtain 1956, credit © Saul Leiter Foundation

One of Leiter's contributions is that he brought a new aesthetic to street photography, using color film in the early '50s, long before it was appreciated in the art scene of the ’70s. For a long time, color was not considered in fine art photography, because the film was expensive and unpredictable in printing. This led many artists to use black and white film, creating the conviction that color film was less artistic. However, Leiter photographed for a long time in color, often using expired Kodachrome film, which gave the photographs a particular hue. For this reason, he is considered a pioneer of color photography. Leiter developed his visual grammar, turning ordinary everyday moments into beautiful abstract images. "I admired a tremendous number of photographers, but for some reason I arrived at a point of view of my own."

Saul Leiter, Snow 1970, credit © Saul Leiter Foundation

Saul Leiter, Postmen 1952, credit © Saul Leiter Foundation

Saul Leiter refused to explain his work. "I don’t have a philosophy, I have a camera." But in return he left us a lot of beautiful expressions that show the nature of an unconventional artist. In an interview he states: “We live in a world full of expectations, and if you have the courage, you ignore the expectations. And you can look forward to trouble.” And Leiter's nature had been unconventional since in his youth, when at the age of 22 he abandoned his theological studies and against his family's wishes he moved to New York from his native Pittsburgh to become a painter. There he found affinity with Abstract Expressionism. After contacts with expressionist painter Richard Pousette-Dart and photographer W. Eugene Smith, he began to take photographs to earn money. The first photos are in black and white of friends and urban scenes. In the 1950s, curator Edward Steichen presented Leiter photographs at the Museum of Modern Art: in 1953, in the exhibition Always the Young Strangers, and in the 1957 slide lecture Experimental Photography in Color. Leiter worked as a fashion photographer for Harper's Bazaar, Elle, British Vogue, and other magazines, where he developed a style similar to his street photography.

Saul Leiter, Mary circa 1947, credit © Saul Leiter Foundation

Saul Leiter, Harper's Bazaar circa 1960, credit © Saul Leiter Foundation

Saul Leiter, Reflection 1958, credit © Saul Leiter Foundation

In the 1980s, Leiter faced financial difficulties and was forced to close his commercial studio. For two decades he worked in silence, painting and photographing in his East Village neighborhood. “I spent a great deal of my life being ignored. I was always very happy that way. Being ignored is a great privilege. That is how I think I learned to see what others do not see and to react to situations differently. I simply looked at the world, not really prepared for anything.”

Saul Leiter, Harlem 1960, credit © Saul Leiter Foundation

Saul Leiter, Mirrors circa 1958, credit © Saul Leiter Foundation

Leiter’s street photography gained attention 50 years after he created many of his works, with the publication of his first book, Early Color, in 2006, followed by the two-volume set Early Black and White in 2014 and the nudes collection In My Room in 2018, along with a series of exhibitions.

The studio of Saul Leiter in New York's East Village, where he worked and lived from 1952 until the end of his life in 2013, has now become home to the Saul Leiter Foundation, which aims to preserve and promote the art and legacy of the photographer. The archive includes thousands of prints, slides, negatives, and paintings, many of which have not yet become known to the public..

Editorial note: We thank the Saul Leiter Foundation for the images provided and assistance in selecting the information: https://www.saulleiterfoundation.org

Sources for Saul Leiter quotations:

Documentary movie from Tomas Leach, In No Great Hurry: 13 Lessons in Life with Saul Leiter:

Interviews:

Saul Leiter in Conversation with Vince Aletti, May 2013

Part 1 - Lecture by Saul Leiter: New York Reflections

Part 2 - Lecture by Saul Leiter: New York Reflections

Part 3 - Lecture by Saul Leiter: New York Reflections

Part 4 - Lecture by Saul Leiter: New York Reflections

podcast from 2006 interview with Mitch Teich on WUWM’s Lake Effect radio show

Walker Evans

Walker Evans is the American photographer who has influenced more than any other the modern documentary photography of the 20th century. With his anti-conformist nature, he rejected the prevailing pictorialist view of artistic photography, supported by the main proponent Alfred Stieglitz, and constructed a new artistic strategy based on the description of common facts in a detailed and poetic manner. Evans has been described as the photographer with the sensibility of a poet and the precision of a surgeon…

Walker Evans

(USA 1903-1975)

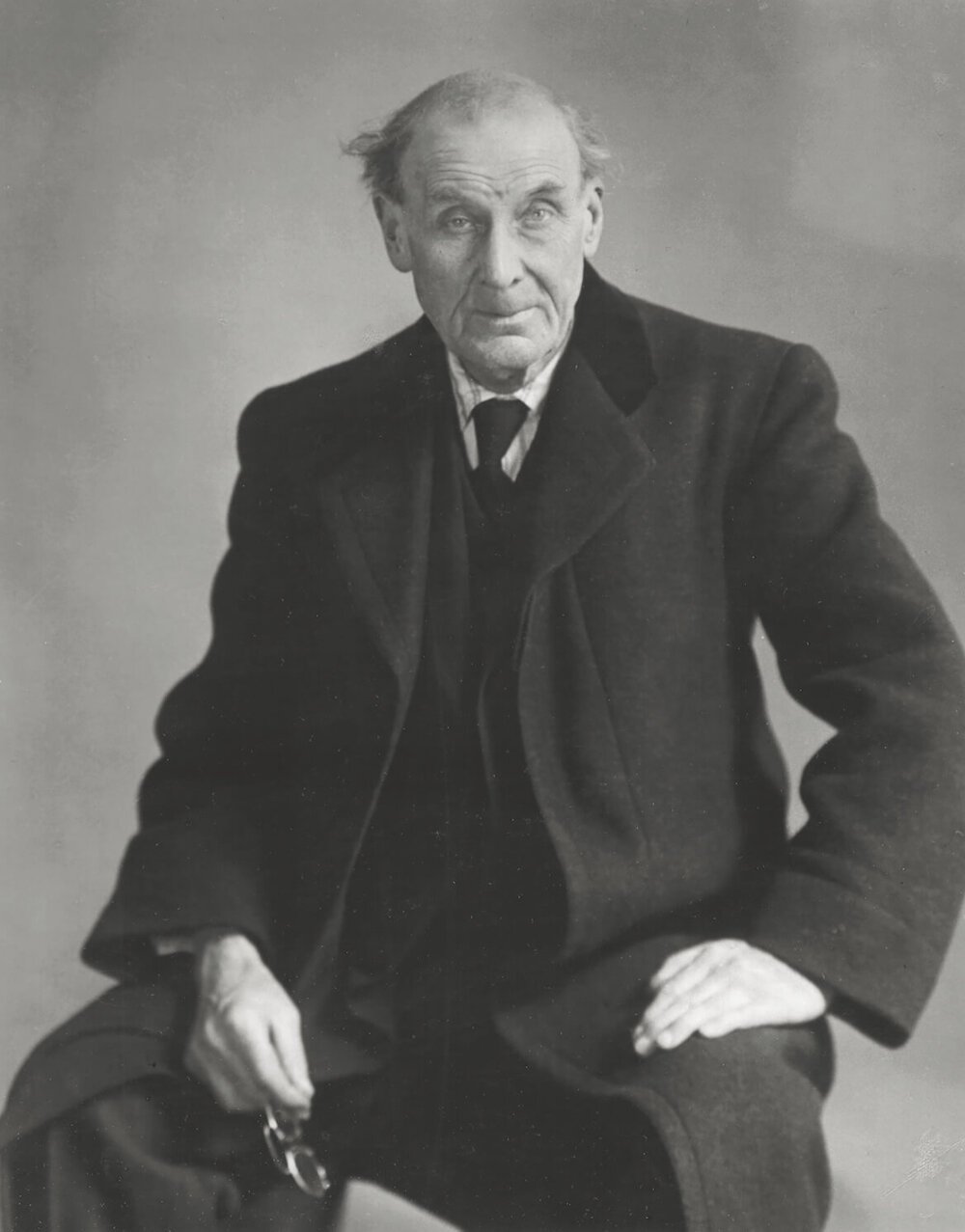

Walker Evans, selfportrait 1930

Walker Evans is the American photographer who has influenced more than any other the modern documentary photography of the 20th century. With his anti-conformist nature, he rejected the prevailing pictorialist view of artistic photography, supported by the main proponent Alfred Stieglitz, and constructed a new artistic strategy based on the description of common facts in a detailed and poetic manner. Evans has been described as the photographer with the sensibility of a poet and the precision of a surgeon… Following independently his artistic strategy, he built a body of work based on the description of American everyday life. His preferred subjects are the vernacular architecture, street scenes, advertising, billboards, shop windows, passers-by, automobile culture, and most important the description of American poor conditions during Great Depression. Evans is the first photographer that the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) New York dedicated a personal photography exhibition in 1938. He was an independent and authoritative figure in photography. For two decades he worked as an editor and writer for Time and Fortune magazines, where he designed the layout and the accompanied words of his photography. In the end of his career he taught photography at Yale University. His photography has influenced a generation of photographers, such as Robert Frank, Le Friedlander, Garry Winogrand, Diane Arbus, the Bechers, and other genres of art, such as: cinematography, theater, and literature.

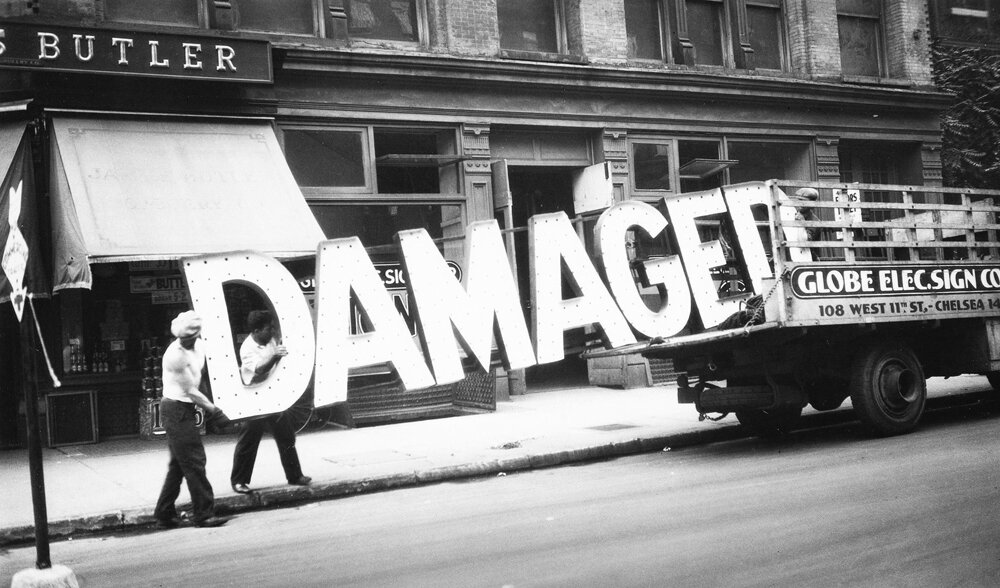

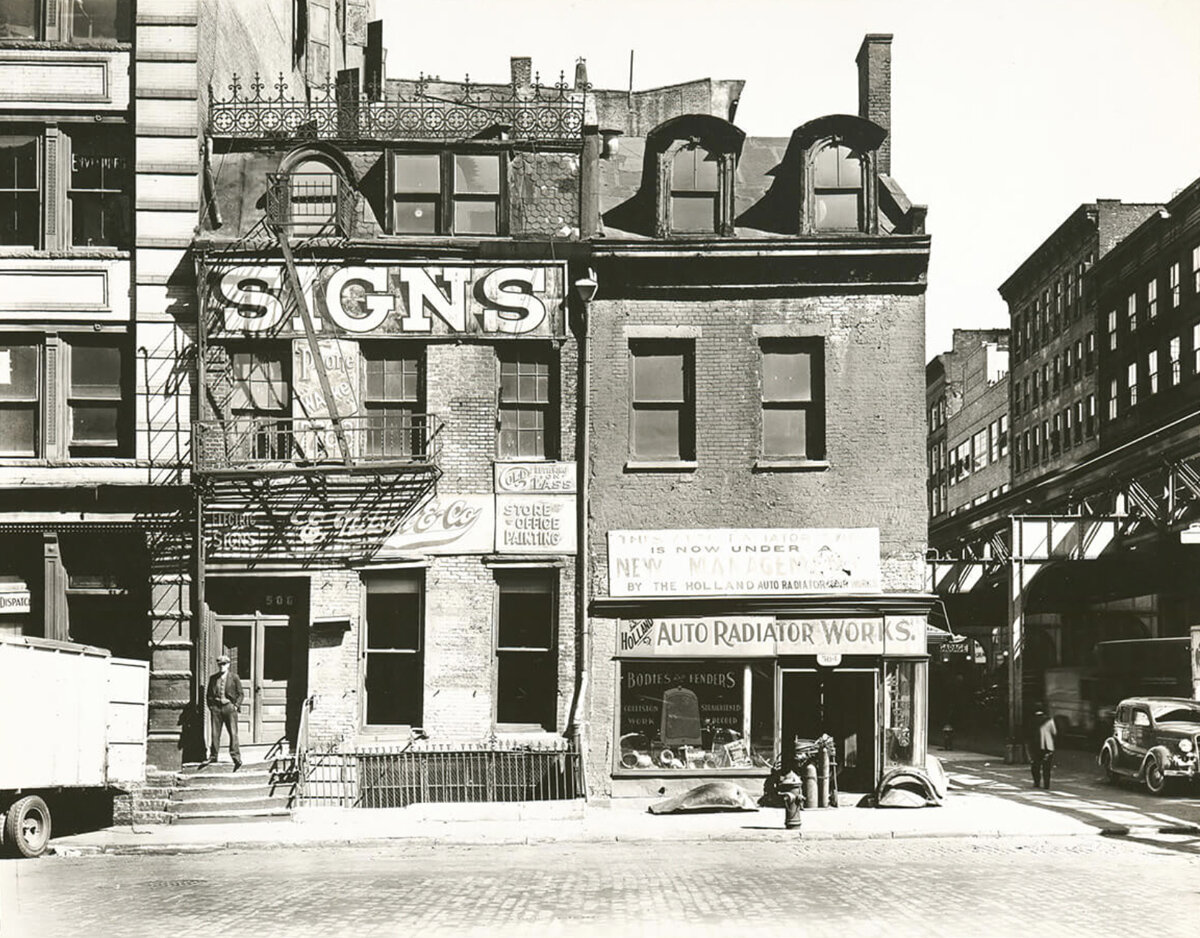

© Walker Evans, Truck and Sign New York, 1930

The first years

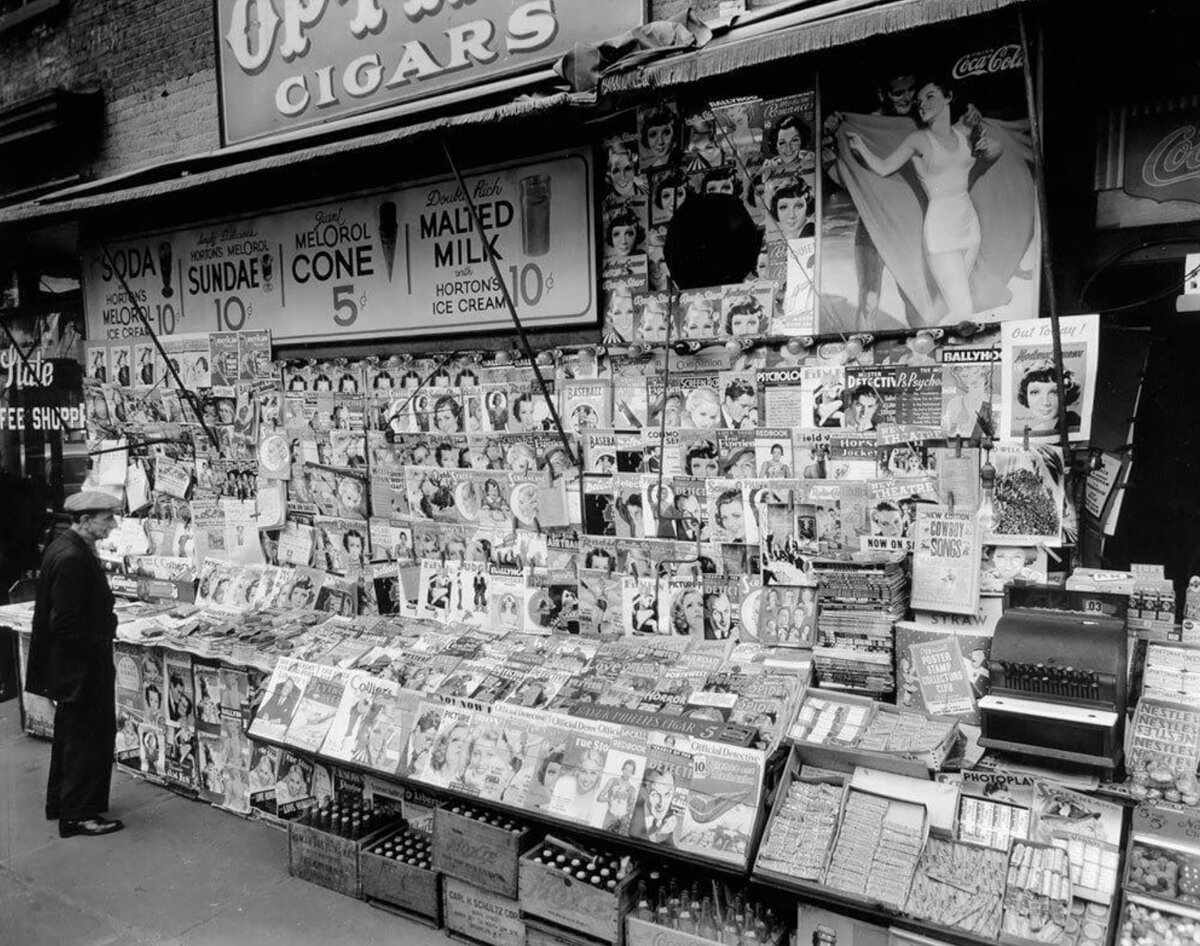

Walker Evans began photographing at the age of 25, with his Kodak handheld camera, during his stay in Paris, where he was studying French literature at the Sorbonne University. Evans aspired to become a writer, but upon his return to New York in 1928, he exchanged the writer's dream for the profession of the photographer. The first photographs are scenes of everyday American life and urban environments: New York streets, Victorian buildings, Brooklyn Bridge, abstract compositions of emerging new architecture, street advertisements, and storefronts. Repeating motifs in his photography are: letters, signs, numbers in billboards and road advertisements. He documented the city through the eyes of a historian and anthropologist, finding what was authentic and American in character. The main influences in his photography were: Eugene Atget and August Sander; while the favourite writer: Gustave Flaubert, from whom he adopted the saying: "An artist must be in his work like God in Creation, he should be everywhere felt, but nowhere seen”.

© Walker Evans, Brooklyn Bridge New York, 1929

© Walker Evans, U.S. Rubber Sign, New-York, 1928-1929

© Walker Evans, Movie Poster, New York, 1930

© Walker Evans, Parked Car, Small Town Main Street, 1932

© Walker Evans, Street Scene with Telephone Pole and Lines, Provincetown Massachusetts, 1931

© Walker Evans, Chrysler Building, 1930

© Walker Evans, Construction Shack, New York, 1929

Havana

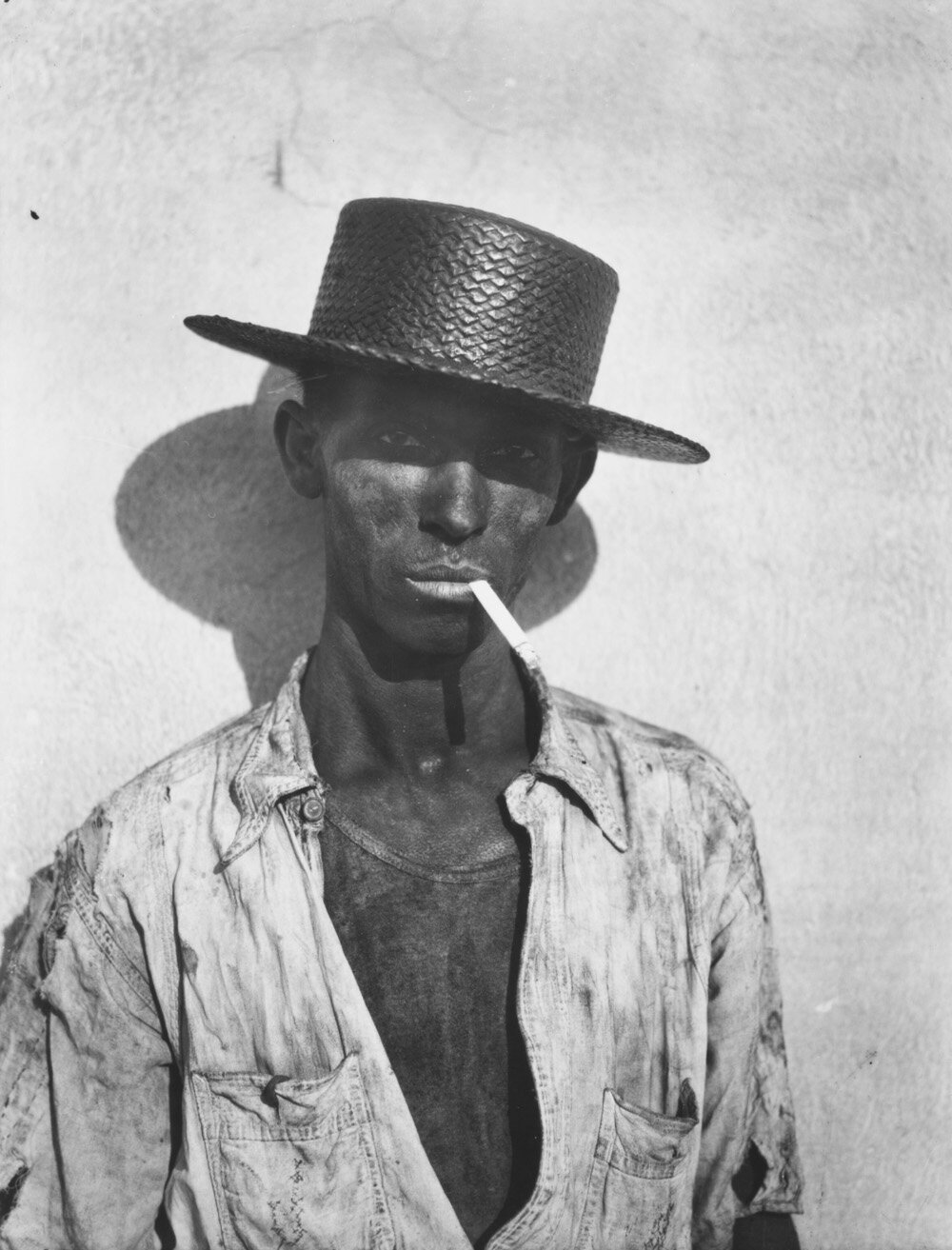

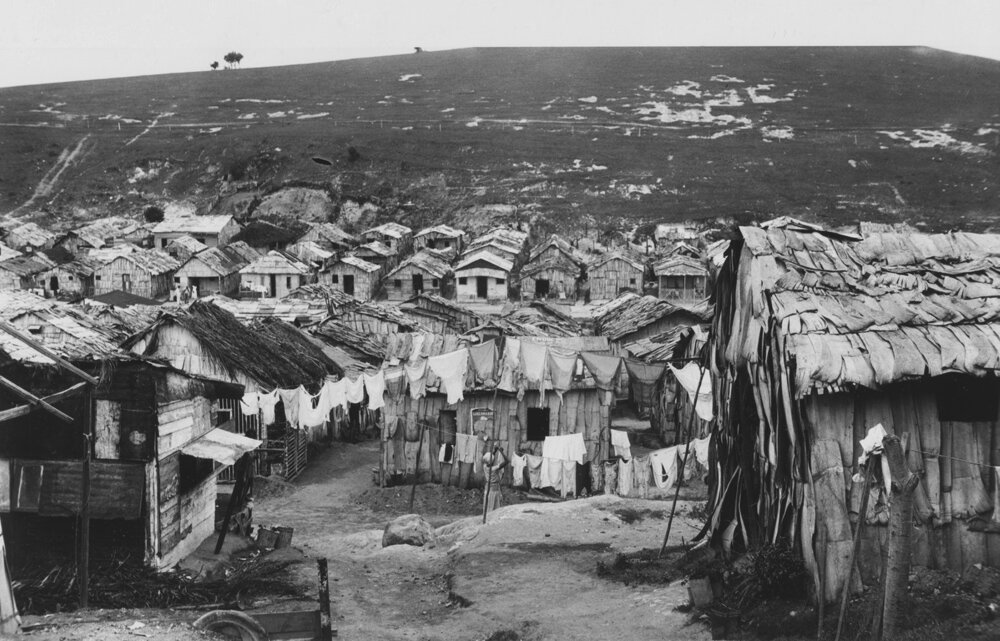

In the early 1930s, Evans was sent to Cuba to photograph the worker’s conditions during the dictatorship of Gerardo Machado. Here he photographed the slums, the street beggars, the police, the port workers, developing the human side of his latter photography. The photographs were published in 1933 in the book “Crimes of Cuba”.During his stay, Evans accompanied Ernest Hemingway, to whom he left 46 photographic prints for fear of being confiscated by the Cuban authorities. These prints were found in Havana in 2002, and were presented in a photographic exhibition.

© Walker Evans, Cinema Havana, 1933

© Walker Evans, Havana Dock Worker, 1932-1933

© Walker Evans, Squatters Village Cuba, 1933

Years of the Great Depression

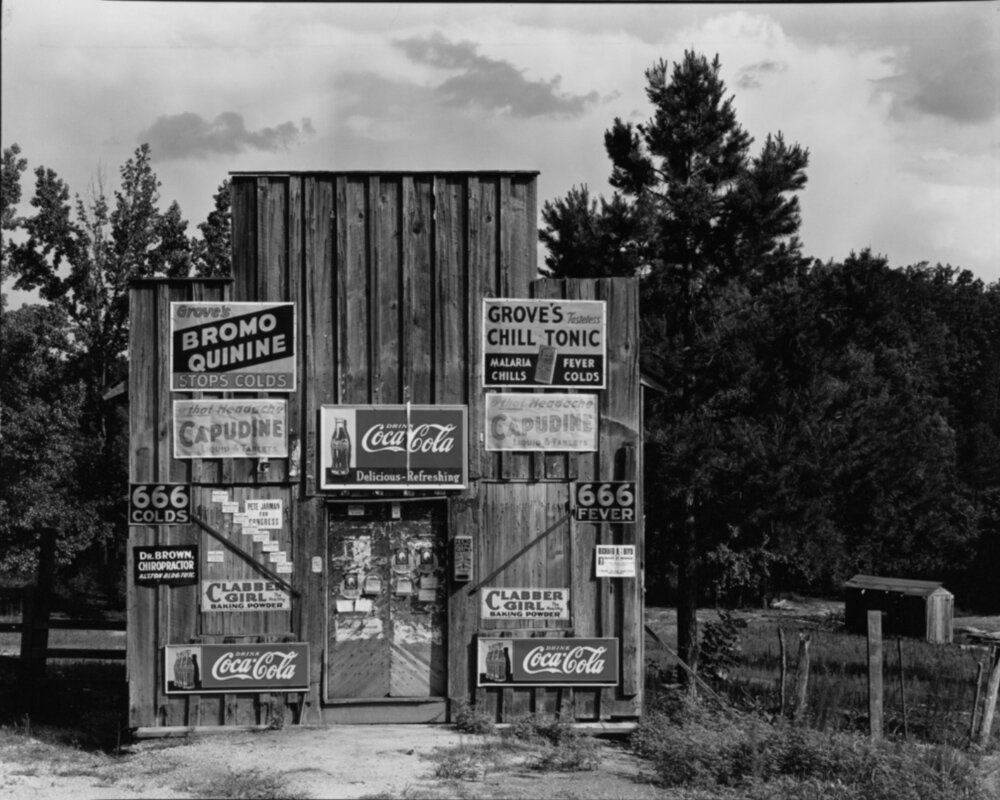

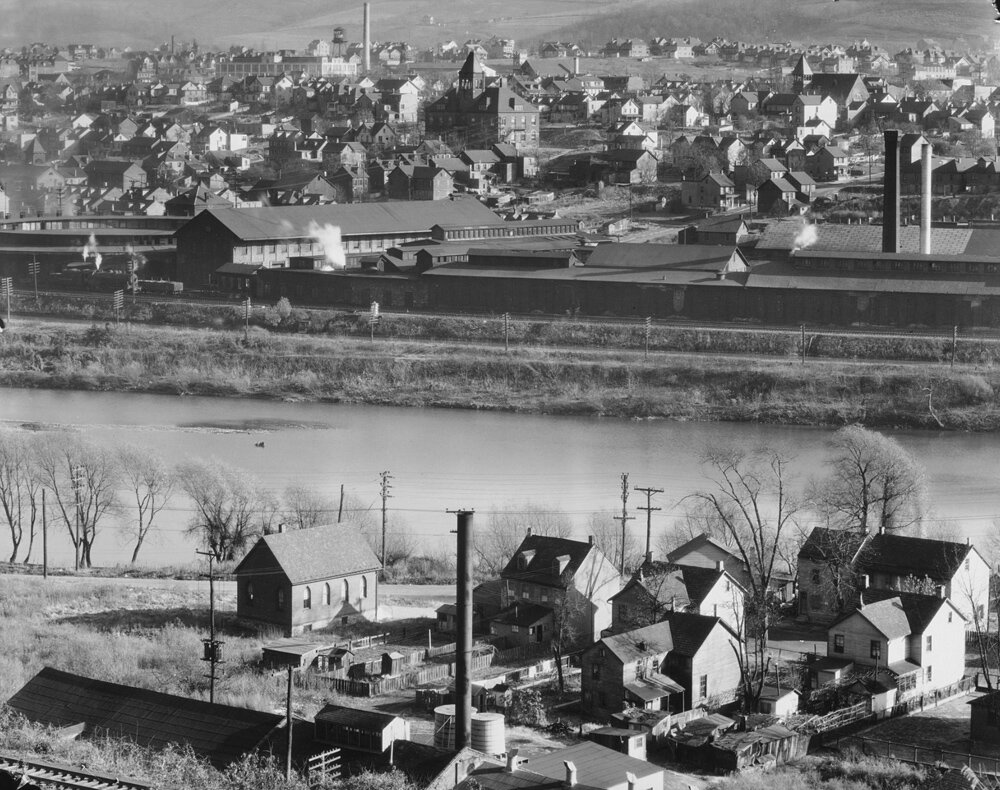

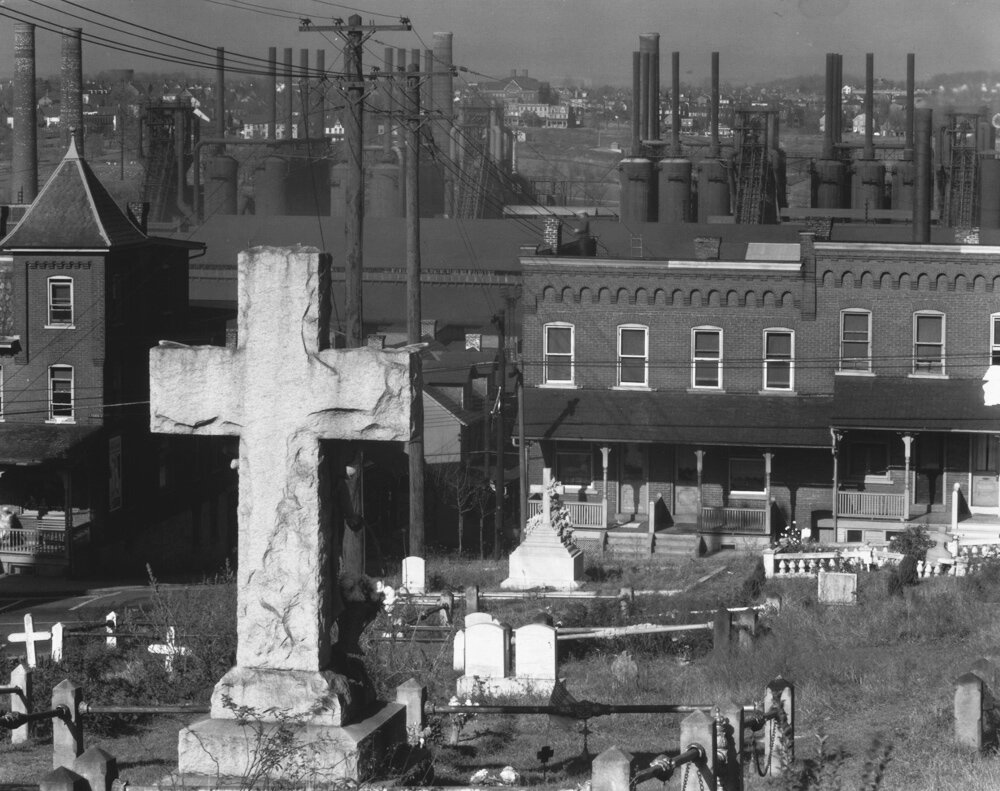

During the years 1935-1937 Evans worked for the government's New Deal Resettlement program (later called the Farm Security), to document the life of South American farmers during the Great Depression. In this project he developed his artistic style to documented the facts in a detailed precise and neutral way, using a large format 8x10 inch camera. A collection of his works was displayed at the Museum of Modern Art in 1938 entitled "American Photographs", which is the first personal exhibition that MOMA dedicated to a single photographer. The book of the same title with 100 photographs by Evans, accompanied with a critical essay by Lincoln Kirstein, remains today one of the most influential books in the history of modern photography.

© Walker Evans, Roadside Store between Tuscaloasa and Greensboro, Alabama-1935

© Walker Evans, Easton Pennsylvania, 1935

© Walker Evans, Breakfast Room at Belle Grove Plantation White-Chapel, Louisiana, 1935

© Walker Evans, Houses and Billboards Atlanta, 1936

© Walker Evans, View of Easton Pennsylvania, 1936

© Walker Evans, Graveyard and Steel Mill Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, 1935

© Walker Evans, Birmingham Steel Mill and Workers Houses, 1936

Let Us Now Praise Famous Men

During 1936, Evans undertook a trip to the South, with the writer and friend James Agee, to document the difficult lives of three sharecropper families affected by the economic crisis. The project, which was rejected for publication by Fortune magazine, was published in 1941 in the form of a book of pictures by Evans and text by Agee, entitled "Let Us Now Praise Famous Men". The photos of this project remain iconic images of America affected by the Great Depression.

© Walker Evans, Coal Miner's House West-Virginia, 1936

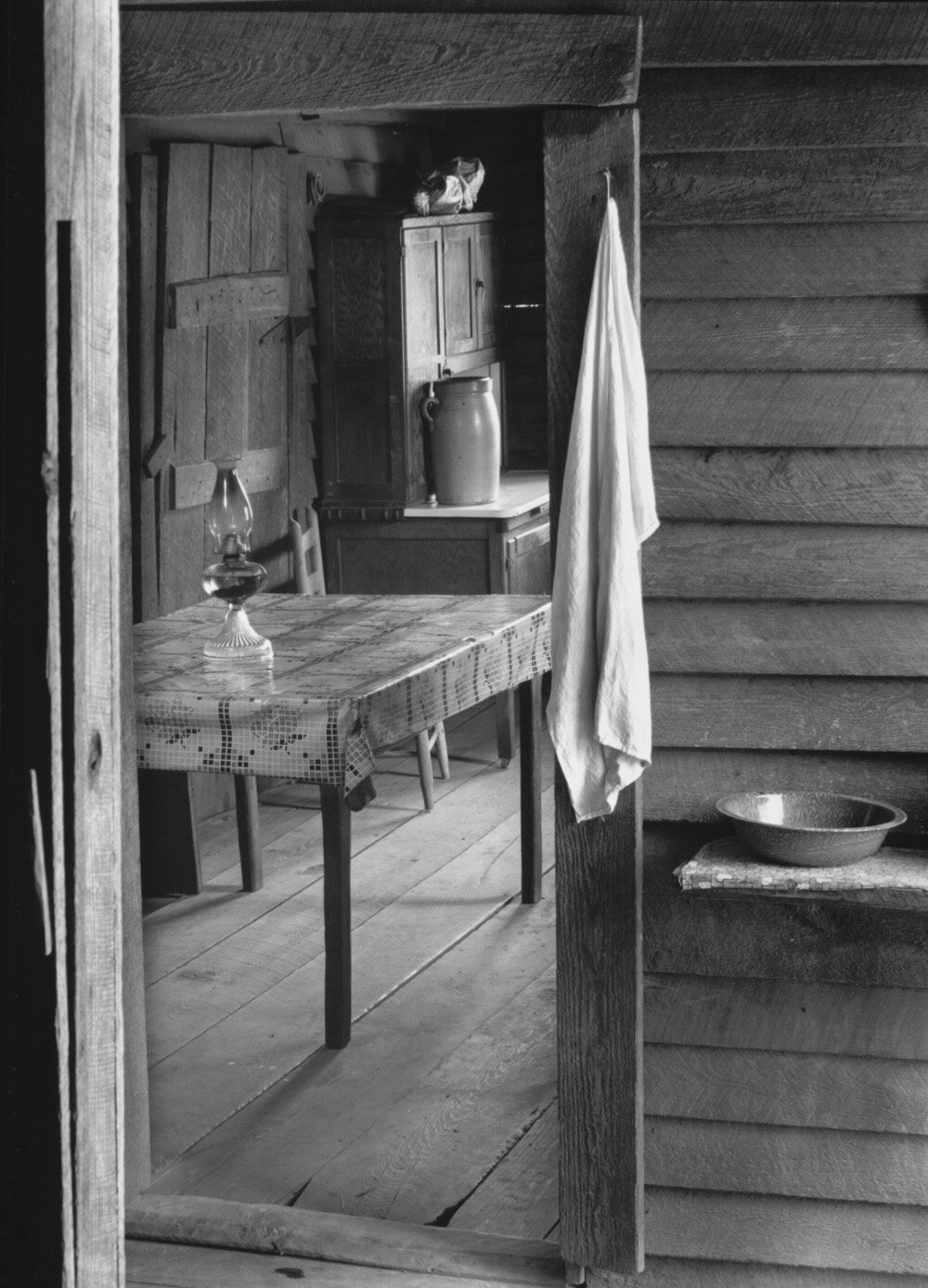

© Walker Evans, Farmers Kitchen Hale-County Alabama, 1936

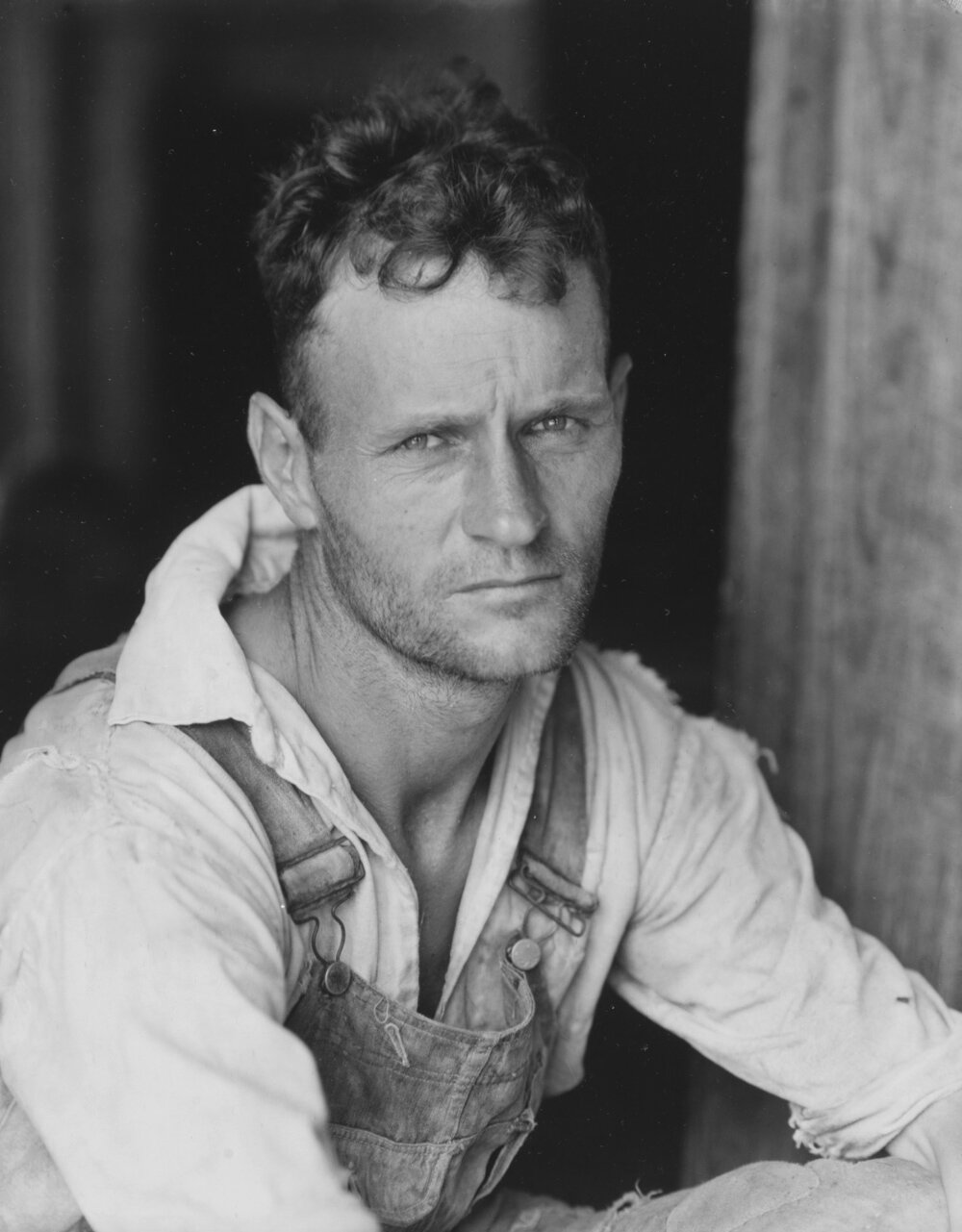

© Walker Evans, Sharecropper Hale-County Alabama, 1936

© Walker Evans, Church Organ and Pews, Alabama, 1936

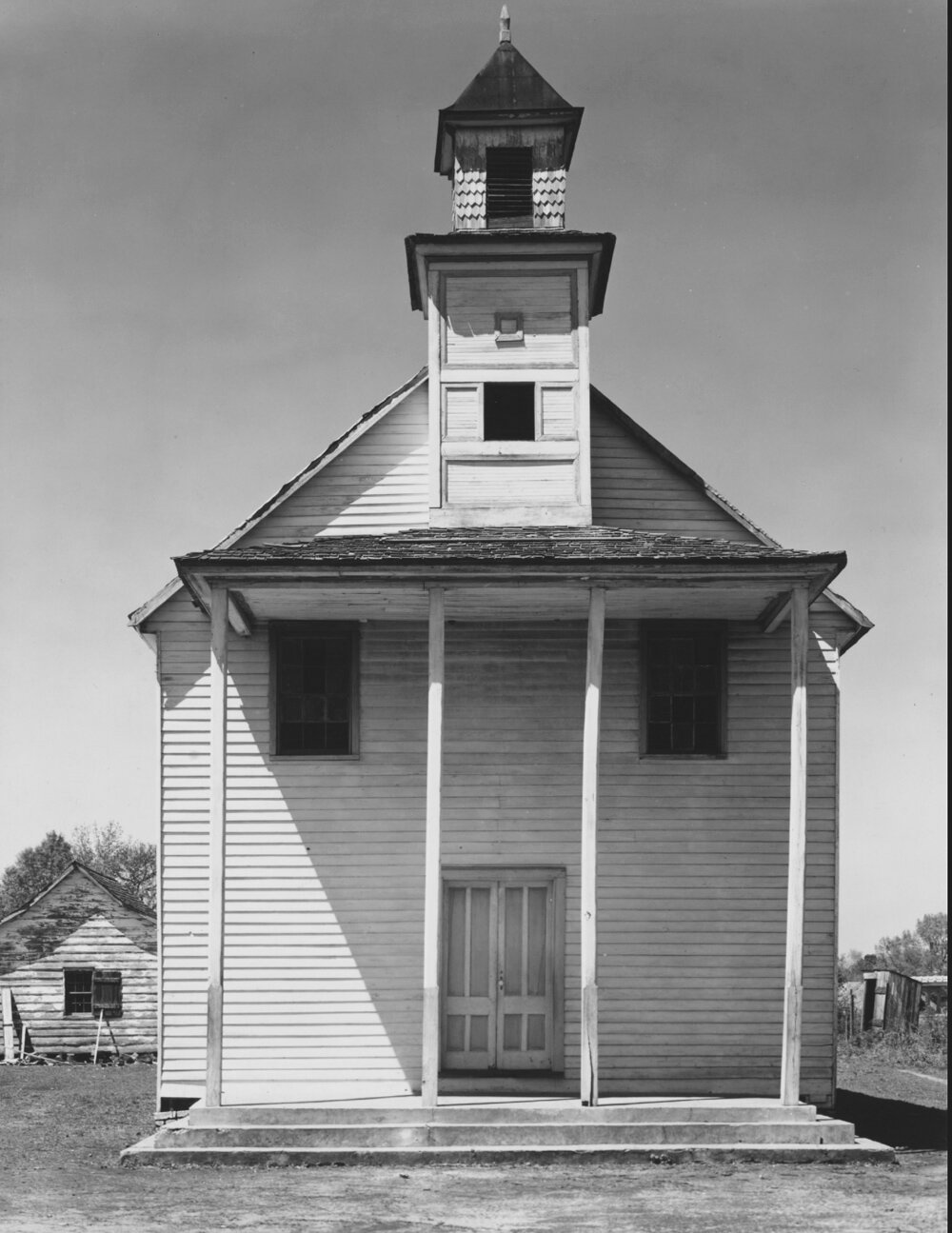

© Walker Evans, Negro Church South Carolina, 1936

© Walker Evans, Barber Shop Vicksburg Mississippi, 1936

© Walker Evans, Country Store and Gas Station, Alabama, 1936

© Walker Evans, Roadside View Alabama Coal Area Company Town, 1936

© Walker Evans, Roadside Stand near Birmingham, Alabama, 1936

© Walker Evans, Window Display Bethlehem Pennsylvania, 1935

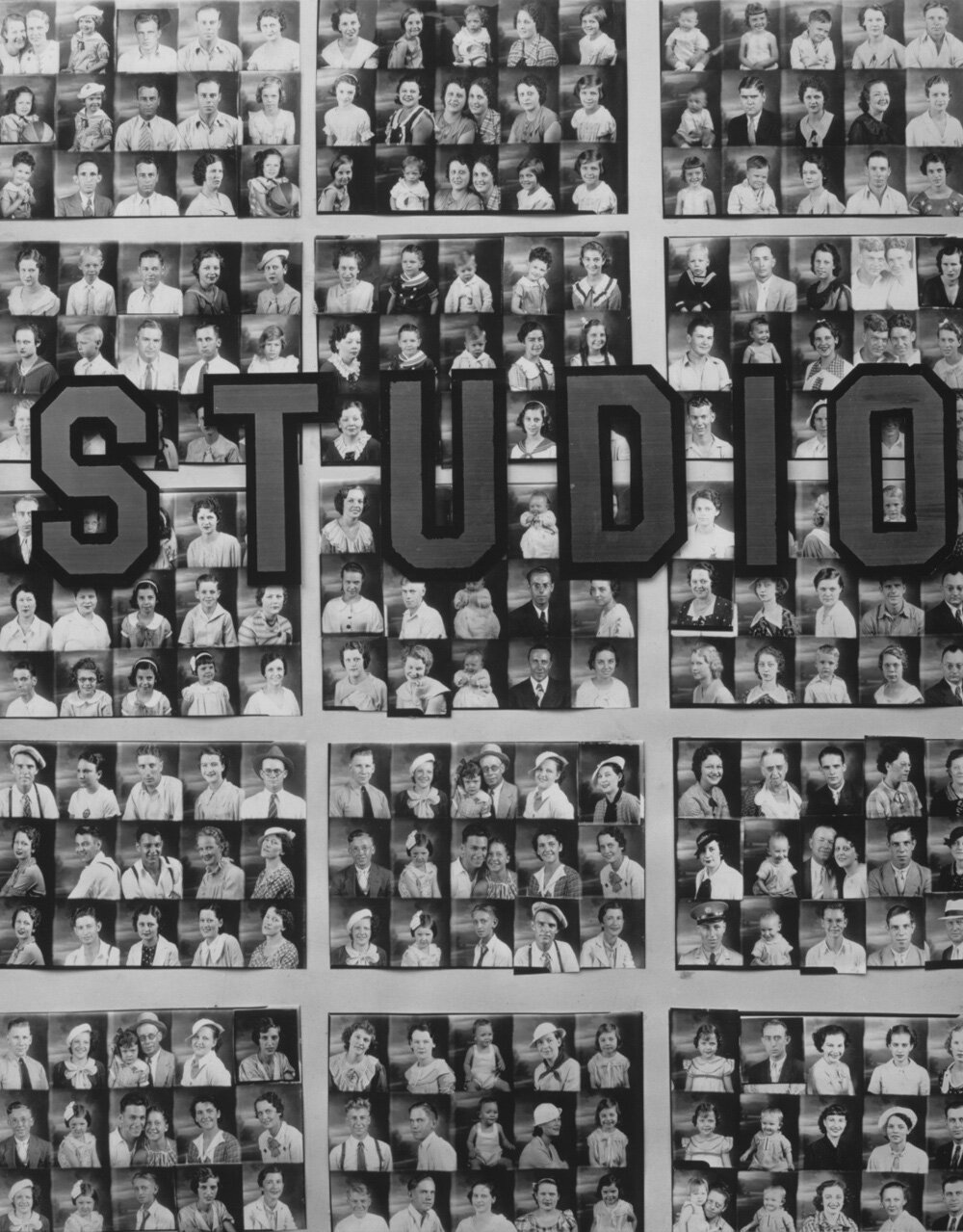

© Walker Evans, Penny Picture Display, Savannah 1936

Subway Portraits

From 1938-1941, Walker Evans photographed New Yorkers on the subway, captured by his Contax 35mm camera, hidden under his coat. The photographic series was published many years later (1966), under the title "Many are called".As he puts it, he wanted to photograph people "when the guard is down and the mask is off." The motif of casual passers-by, is a recurring motif in Evans work. While working for Fortune in 1946, he photographed with Rolleiflex a series of portraits of workers on the streets of Chicago, which are published in 2 pages of the magazine under the title "Labor Anonymous".

© Walker Evans, Subway Portrait, 1938-1941

© Walker Evans, Subway Portrait, 1938-1941

© Walker Evans, Labor Anonymous, Fortune November 1946, pp152-153

Years in Time and Fortune Magazine

Evans worked for Time magazines (1943-1945), and later for Fortune (1945-1965) as a photo editor, producing over 400 photos and 46 articles. Evans had complete control over the publication of his photographs, he chose the subjects himself, the accompanying writings and the layout of the magazine. Having photographed America at its most difficult years, now Evans captures its rise as the world superpower, the culture of automobile and consumerism.

© Walker Evans, Burlesque Theater, Chicago 1946

© Walker Evans, Views of Pedestrians Uniontown, Maryland, 1946

© Walker Evans, Pedestrians Uniontown Maryland, 1946

© Walker Evans, Shoppers Randolph Street, Chicago 1946

© Walker Evans, Untitled Chicago, 1946

© Walker Evans, Lamp on Table, Evans Apartment New-York, 1946

© Walker Evans, Details of Clapboard House, 1960

Last years

In 1965, Evans began teaching photography at Yale University School of Art and Design. During the ’70s he experimented with colour photography, and the Polaroid SX-70 camera, with an unlimited supply of film from Kodak. These photographs are interesting studies of colour and shape, on Evans' preferred motif: architecture, portraits and signs.

© Walker Evans, New-York Streets, 1957-1959

© Walker Evans, New-York Streets, 1957-1959

© Walker Evans, Telephone Pole and Red Barn, 1974

Walker Evans's photographs are in the collections of:

Selected Books by Walker Evans

W. Eugene Smith

W. Eugene Smith was an American photographer, known as the father of photo essay in the American editorial of the '40s and '50s. He created the genre’s model and standards that were followed for a long time. Eugene Smith worked for several magazines of the time such as: Newsweek, Life, and for the agency Magnum as a freelancer.

W. Eugene Smith

(U.S.A 1918-1978)

Portrait of W. Eugene Smith. Photograph by Fran Erzen

W. Eugene Smith was an American photographer, known as the father of photo essay in the American editorial of the '40s and '50s. He created the genre’s model and standards that were followed for a long time. Eugene Smith worked for several magazines of the time such as: Newsweek, Life, and for the agency Magnum as a freelancer. His most famous photos essays are (in chronological order): World War II (1943), Country Doctor (1948), The Midwife (1951), The Spanish Village (1951), Man of Mercy (1954), Pittsburg (1955), Jazz Loft (1965), Minamata (1971).

During his career in photography, Eugene Smith is distinguished for his humanism, the need to know his subjects well, the perfectionism and anti-conformism to the dictate and boundaries set by the mass media. More than a photojournalist, he is a director of storytelling and a poet of photography through the use of light and chiaro-scuro.

US Marine World War II. Photograph by W. Eugene Smith

A Hospital in a Philippine Cathedral (Island of Leyte). Photograph by W. Eugene Smith

“The walk to Paradise garden” 1946, Photography W. Eugene Smith

“Country Doctor, Ernest Ceriani”, 1948, Photography W. Eugene Smith

His most important photo essays addressing the theme of urbanisation and consequences of industrialisation are; Pittsburg (1955) and Minamatas (1971).

Eugene Smith began photographing Pittsburgh in 1955 when writer and publisher Stefan Lorant asked him a series of photographs to illustrate his book on the city's 100th anniversary. Smith saw this commission as a personal project. He extended the duration of the project from three months to three years, and expanded the subject by photographing the modernity and the steel industry, as well as other topics that did not belong to government propaganda, such as working class conditions, poor neighbourhoods, the immigrants, the African American community, preceding the riots of the 1960s. In this project, Smith built a rich archive consisting of 17,000 photographic images and audio recordings, a small part of which have been published.

Inside Mellon National Bank. Photograph by W. Eugene Smith.

International Union of Electrical, Radio, and Machine Workers. Photograph by W. Eugene Smith

City Council Chamber, Pittsburg, © Photography W. Eugene Smith

Children at Colwell and Pride Streets, Hill District. Photograph by W. Eugene Smith

Pittsburg, 1955, Photography by W. Eugene Smith

Sixth Street Bridge over Allegheny River. Photograph by W. Eugene Smith

Steelworker wearing goggles and a hardhat. Photograph by W. Eugene Smith

Rails, Homestead works, U.S. Steel, Monongahela River. Photograph by W. Eugene Smith

US Steel Pittsburg, 1955 Photograph by W. Eugene Smith

Pittsburg 1955 Photograph by W. Eugene Smith

In Minamata series (1971-1973), Eugene Smith photographs the inhabitants of Minamata coastal area in Japan affected by a severe disease caused by mercury in the industrial waste of Chisso factory, a giant chemical industry in the area. In 1972, Smith was attacked by Chisso Company, to stop the publication of the project on Minamata disease, which caused him severe injuries and loss of vision. The photo essay was published in 1975 and its main photo was ‘Tomoko Uemura in Her Bath”, shot in 1971, showing a mother in a traditional Japanese bathtub, with her daughter deformed by the disease. The photo drew public attention to the Minamata disease. Smith's photographs were the main evidence in the trial against Chisso, and the first case in Japan where a company became liable of the damages it caused to the people, which made Smith a national hero in Japan.

Minamata, 1972 Photography W. Eugene Smith

Minamata 1971 Photograph by W. Eugene Smith

Goi, near Tokyo. Demonstration at the Chisso Plant. 1971 Photograph by W. Eugene Smith

Demonstrators against the Chisso Chemical Company demonstrating in front of the plant near Tokyo during the Pollution Board hearings. 1971. Eugene Smith

After Minimata project, Eugene Smith returned to America, but was not able to photograph anymore. He taught at university and arranged his archive until 1978, when he died of a heart attack. Eugene Smith believed in the power of photography to change the world. In 1980, the Eugene Smith Fund was established to finance humanitarian photographic projects that cannot be funded by the mass media, contributing to the growth of the independent voice of photographers.

W. Eugene Smith Fund: https://www.smithfund.org/humanistic-photography

Selected Books by W. Eugene Smith

Berenice Abbott

Berenice Abbott is an American photographer known for documenting the architecture and metropolitan life of New York with all its contrasts in the ’30s of the Great Depression. She photographed with an 8x10 inch camera the new architecture of New York that was emerging, but also the places that were disappearing from development.

Berenice Abbott

(U.S.A 1898-1991)

Berenice Abbott Portrait

Berenice Abbott is an American photographer known for documenting the architecture and metropolitan life of New York with all its contrasts in the ’30s of the Great Depression. Berenice Abbott is known for her documentary style, outside of any subjectivism and pictorialism. She photographed with an 8x10 inch camera the new architecture of New York that was emerging, but also the places that were disappearing from development. Her main influence was the French photographer Eugene Atget, who scrupulously photographed old Paris, which was disappearing from the modernity of the early 20th century. Abbott called Atget ‘the Balzac of the camera’ and an ‘urban historian’. She is credited with rescuing Atget's archive when, after his death, she bought all the negatives and took them to America, where she worked to publish his work. In the last years of her career Berenice Abbott was involved in the technical and scientific aspects of photography.

One of her expressions is "The world doesn't like independent women, I don't know why, but I don’t care"