Leonard Qylafi

Leonard Qylafi (b. 1980) is an Albanian visual artist, whose practice explores several mediums such as photography, painting, video and music, where the theme of the City and its Architecture occupies a certain role. The Photography and Video Projects that reflect on the transformation of urban spaces are (real) ESTATE, Estate, Whispers & Shadows, Solo Show.

Leonard Qylafi (b. 1980) is an Albanian visual artist, whose practice explores several mediums such as photography, painting, video and music, where the theme of the City and its Architecture occupies a certain role. The Photography and Video Projects that reflect on the transformation of urban spaces are (real) ESTATE, Estate, Whispers & Shadows, Solo Show. Deeply linked with personal experience, Leonardi's artworks are a process of research and meditation between subjects and mediums. Since his graduation from the Academy of Fine Arts in Tirana, the Atelie of Painting 2003, Leonard Qylafi has been present in the local and international art scene. During the last years his works have been shown in several galleries and international events, such as: Centre de création contemporane, Olivier Debré, Tours-France (2021); Belvedere 21 Vienna, Austria (2019); NiMAC Cyprus (2018); National Gallery Tirana, Albania (2017); MuCEM, Marseilles, Izolyatsia, Kiev in (2016); The 55th October Salon, Belgrade (2014); Künstlerhaus Bethanien, Berlin and Kunst Raum Riehen Basel/Switzerland (2012); MODEM Centre for Modern and Contemporary Arts, Debrecen, Hungary (2011); TICAB-Tirana International Biennial of Contemporary Art, Bjcm- XIII Biennal of young artists from Europe and Mediterranean, Puglia, Italy and ISCP- New York /USA in (2009) among other places. His work is published internationally and is collected by; The Albanian National Gallery of Art, MuCEM- Musée des Civilisations de l'Europe et de la Méditerranée, Marseille; Contemporary Art museum Belvedere 21, Vienna, video collection and several private collections. In 2017, Leonard Qylafi represented Albania in the 57th edition of the Venice Biennale, with the multidisciplinary project "Occcurrence in the Present Tense" curated by Vanessa Joan Müller. I am very pleased that Leonardi accepted to be interviewed for Tatì Space and talk about his projects in regarding Architecture and Urban Photography.

Alketa Misja for Tatì Space: Hello Leonard. You are a visual artist who explores several mediums, among them Photography and Video. What is the place Photography occupy in your artistic practice? How did you become interested in Urban and Architecture Photography?

Leonard Qylafi: My interest in photography came when I was studying at the Academy of Arts, in the painting atelie. Until then I had an art school education, focusing on drawing and painting. Photography was new to me and took time to master technically and use as a medium for special projects. What I can say is that it has had a huge impact on my practice as an artist either directly or indirectly and remains present in my work. Mainly, special projects that I have realized in photography have always been solutions started from a conceptual approach. In the case of urban photography, it has naturally been part of projects that focuse on urban transformations.

Tatì Space: What is your approach, in respect to Architecture and Urban Photography? You have several projects about the new construction in a rapidly growing city like Tirana. What is the idea, the concept behind these works?

Leonard Qylafi: I have been dealing with urban photography mainly in function of the artistic projects that I have developed. Around 2007-2011, urban space has taken an important place in my projects. The (Real) Estate and Estate projects are based entirely on photography, even though Estate is a photo animation turned into a video. Other projects always with the same theme have been in the form of videos such as Private Show or Whispers&Shadows. In each of them, a special aspect of the relationship we have with the space we live in is addressed, and in particular the idea of change and memory in relation to what we call Polis or city, as a complex entity and an expression of the culture and worldview of human society.

Tatì Space: How do you see the artistic scene in Albania in relation to Urban Photography? (if you can share an opinion). The photo can provoke a thought or nurture a discussion about city's problems. In this sense, what advice can you give to young photographers who want to explore urban and architecture photography?

Leonard Qylafi: Looking at the artistic scene in a general view, I can say that unfortunately there is a total lack of spaces, structures that are necessary for the promotion and exposure of art as a whole and of course contemporary photography. This makes it difficult to recognize and introduce new artist-photographers. The other part that makes it even more difficult, in the case of photography in particular, is its massification as a practice with the development of technology. It would be necessary to create special structures with a focus on photography. Regarding urban and architectural photography, I can say that Tirana today is a very rich subject to explore. I would suggest young photographers to see it as a unique opportunity on which to build their research either in terms of the city as a subject or architecture in particular.

Tatì Space: Thank you Leonard, We wish you all the best for your artistic plans and projects.

Below we give a summary of Leonard Qylafi's works, with regard to Urban and Architecture Photography, focused on theme of City and construction developments.

(real) ESTATE

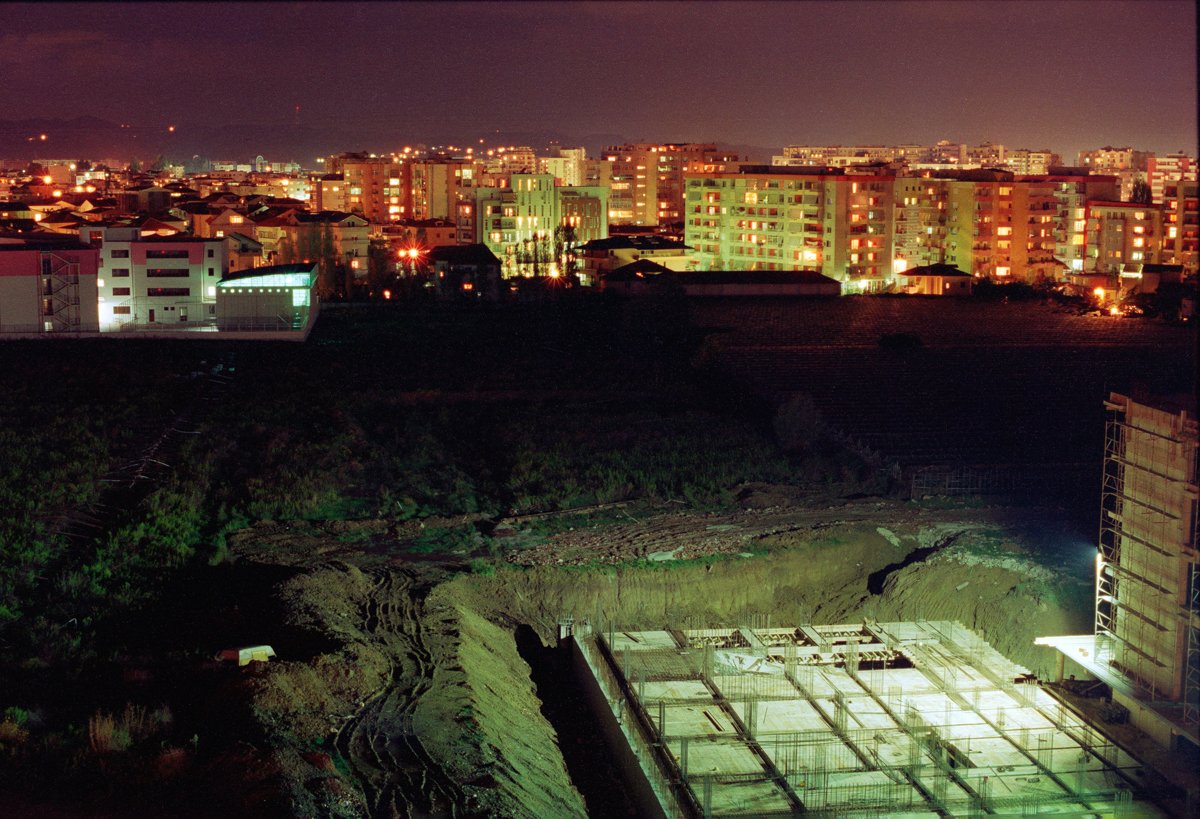

(real) ESTATE, courtesy of Leonard Qylafi

The series of photographs were developed within a three year period and together with the video works Estate and Whispers & Shadows reflect on the transformation of the urban space in Tirana. In this particular project that was the starting point of my research on this topic the documentary style of photography plays the role of the critical awarnes of how the space is transformed. How a different ecomomic and political system overlapes a previous one. The greenhouse use to exist in suburb of Tirana during the communist regime and now is in a middle of a new neighborhood . This masive transformation more than having a shocking effects rises the question of how much do we participate as people living in a city. Do we decide how this city should be shaped to fit our needs ? Unfortunately the people don't play any role but the spectator.

Whispers & Shadows / 2011 / Video installation / Standard Pal 4:3 aspect with sound / 5:24 min/sec

Fragment from the Video installation “Whispers & Shadows” / 2011 / Standard Pal 4:3 aspect with sound / 5:24 min/sec. courtesy of Leonard Qylafi

The ambiance of the site introduces the viewer with the happening; constructions machines excavating in the ground covered by the darkness of the night. Their loud noises give place to a female voice reading selected text by Aristotle’s Politics. The verses which speak about Polis and the sense of living together sound utopia in the today machine-like model of urban centre where the role of the public seems to get eclipsed somehow. The ideal of living together, sharing the goods and the space sounds like millenniums away indeed, once the noise of the machines is firmly back.

ESTATE / 2007 / Video installation / Full HD (no sound) / 8:58 min/sec

Fragment from the Video installation ESTATE / 2007 , Full HD (no sound) / 8:58 min/sec courtesy of Leonard Qylafi

The silent animation lump numerous photographs making this way notes of the construction process of a massive building. The perceptive aspect of the process becomes a key element of the work. The physical time of a two year process of construction is concentrated in nine minutes of animation but it does so by challenging the viewer attention with an apparently freeze look.

Private show / 2006 / Video installation / Standard Pal 4:3 / Music by Leonard Qylafi / 3:19 min/sec

Fragment from the Video installation “ Private show”, 2006, Standard Pal 4:3 / Music by Leonard Qylafi / 3:19 min/sec. courtesy of Leonard Qylafi

The relations we have with places is very complex and somehow impossible to describe in words. In Tirana where I live is very usual to see buildings demolished for building new ones. This violent transformation impacts the life of people living in the city. When you see that a building that you know is demolished the kind of shock you experience can not be described. This was also the case with the building that becomes the stage of my performance. I go there and play a short music piece I have composed as a memoriam to the relation I use to have with that place

To see more about author’s work on his website: www.leonardqylafi.com

Nick St.Oegger

Nick St.Oegger is a documentary photographer whose work explores the relationship between people and places. A quiet American, as he calls himself in his social media, he has been working in Western Balkans since 2013. In Albania, he has a large body of work about a very sensitive issue: the construction of hydropower projects in the rivers of the region known as the “Blue Heart of Europe”, and the impact they have on the rich biodiversity and the unique culture of inhabitants. Here we present the interview that Nick St.Oegger has given to TatìSpace.

Nick St.Oegger is a documentary photographer whose work explores the relationship between people and places. A quiet American, as he calls himself in his social media, he has been working in Western Balkans since 2013. In Albania, he has a large body of work about a very sensitive issue: the construction of hydropower projects in the rivers of the region known as the “Blue Heart of Europe”, and the impact they have on the rich biodiversity and the unique culture of inhabitants.

He has been working for different clients including: Patagonia, Vice, Reuters, Le Monde, Libération, Polityka, De Standaard, Nieuwe Revu, Huck Magazine, Caritas Albania, The Calvert Journal, Suitcase Magazine, Point.51, Trip Advisor, Kosovo 2.0, Riverwatch, C41 Magazine, and Culture Trip. He has exhibited his work and published a book on Vjosa River. From one year now, he lives in Albania. I am very happy that he accepted to give an interview to TatiSpace and share his work with our readers. Below is the interview.

TatìSpace: Hello Mr.Nick! First of all, thank you very much for accepting the invitation to be interviewed and sharing your work with us. Can you please tell us more about yourself? Do you consider yourself a travel or a reporter/ documentary photographer? How do you define your photography? How did the idea or interest to photograph in Albania come to you?

Nick St.Oegger:I grew up in California, but have been living and working around Europe for about 8 years now, mostly here in the Balkans, but also in Ireland and the UK. When I was growing up, I thought I would become a lawyer and this was how I prepared my education and what I was trying to focus on. However, the last year at university I had a bit of a crisis where I realized this wasn’t what I wanted to do. I was interested in photography, but it had always been just a hobby, I hadn’t thought about it as a career option until I discovered the work of some photojournalists who worked in the Balkans in the 1990s, in Bosnia, Kosovo and here in Albania. I was very moved by this work, and the idea of using images to tell a story, to raise awareness about different issues facing individuals and communities. So this is how I started out in this field, this was the moment I knew with every bone in my body that I wanted to be a visual storyteller. I do consider myself a documentary photographer, I am always trying to communicate a story or shed light on a particular issue, and for me photographs are the way that I do this, though writing is also important to my work.

I first came to Albania in 2013, on my first trip to the Balkans. I didn’t know anything about Albania before, and I was mainly interested in seeing the countries of former Yugoslavia. I saw Albania on the map and asked some people about it, everyone had very negative responses like “Oh you shouldn’t go there because it’s run by the mafia” or “It’s dangerous, you’ll get kidnapped” or “Why would you go to Albania? There’s nothing to see!”

I thought about these things as I was planning my trip, and I intended to avoid Albania. I arrived in Istanbul, made my way to Athens where I booked a flight to Venice and I would spend some time afterwards on the coast of Croatia. But the morning I was meant to leave Greece, I woke up and the very first thought which came to me was “Go to Albania.” It’s hard to explain, it was like some sort of vision, or fate. So I missed my flight, instead, I got on the next bus I could find to Albania and the rest is history. It was really a life changing decision, that first trip to Albania: I met amazing people, I saw how beautiful and unique this country is but how little the outside world knows or thinks about it. So it was that trip that I decided to focus my attention on Albania and the Balkans, because it’s a region that many people simply don’t understand, even in Europe.

TatìSpace: Here in Albania, you have a large body of work that includes a vast geographical area (from North to South), and a variety of themes (from bunkers to rivers to the Albanian Alps). From these, I can identify two main projects that are very sensitive to the Albanian public interest: “The Lament of the Mountains” and “Kuçedra”. What started out the idea to work on these projects? Was it commissioned or was it a personal project?

Nick St.Oegger: Yes, both these projects are long-term personal projects that I started on my own and then received further support for. Both of these projects started in a rather organic way. When I first came to Albania, I remember taking the bus from Gjirokastër to Tirana, and passing the Vjosa at Tepelenë. I remember the colour of the water; it was like nothing I had seen before. Several years later I was reading a magazine back in the US and I came across a short article about the Vjosa, how it was one of the last free flowing rivers in Europe, but that the government was planning to build dams on it. I realized this was the river I had seen on my first trip, and I felt a strong desire to return, to document the river, the landscapes, the people along its course. Again, it was this sense of fate, I think. In working on the project I now feel this very strong connection to the Vjosa, and whenever I return it feels like visiting an old friend.

Similarly, “Lament of the Mountains” was produced several years later, after I met an anthropologist who was working in the Kelmend region and she told me about the situation of the rivers there; that they are also building these small hydropower dams. She told me about the culture in the valley, how people are still so connected to the land, how they move with their sheep to the high pastures in the summer. I felt like this was another story I had to tell, because for me the mountains are such an important part of Albania, as well as this very strong rural culture and connection to the land.

TatìSpace: In both projects there is an interconnection between the general view (environmental, political, economical) and the personal view (the impact that the projects have on people’s lives). This gives them an intricate beauty. You skip from landscape photography of large panoramas to close up portraits of mountaineers and peasants living near Vjosa. Have you found difficulty approaching this kind of photography? Can you share an episode that impressed you in particular, for example meeting with villagers or authorities? Also, did you have any problems or incidents with groups or individuals that supported the dam projects?

Nick St.Oegger:Yes, that’s right, and I think it is precisely this interconnection that is so unique and important in Albania. Outside Tirana, there are still many places in the country that are very rural, where people are still living rather traditional lives, working with the land. Yes, there are negatives that come from this life, such as poverty and other problems, but I think the way that many people still live with the land in Albania is unique, and people take pride in this work, they feel a strong connection to their land and the history behind it. So for me, especially with these two projects, it is very important to show the people in context of the land, to show that it is not just one or the other that is being threatened, it is both, because of the strong interconnection between environment and people in Albania. And this connection is exactly what is being threatened by so many proposals, whether it’s by the government, or foreign investors.

It can be difficult to approach this kind of photography. I spend a lot of time trying to work in small communities, to gain people’s trust, which is hard to do in Albania. I think there is a lot of mistrust, because of the history with communism, but also the recent history. People are used to foreign journalists coming, they take some photos for a few days, and then they leave. I have always tried to build stronger relationships with my subjects, to try to get to know them as humans first. I always try to return when I can, to give them prints of some of the photos I took of them. Another important aspect for me has been learning the Albanian language, which is difficult, but it has opened up so many doors. I think because the language is so important to people here, they trust me more when they see I am trying to speak to them in their own language.

Probably one of the most impressive experiences was when I stayed with the shepherds in Kelmend during the summer. We migrated with a herd of 200 sheep, I walked 40km with them to their shelter near Lepushë. It was beautiful to spend time with them there, to see the way they care for the sheep and their families, to see the way the children help with everything and how much knowledge they have about the environment, the weather, how they take care of themselves and fix things. Before this, the ‘malësorë’ were a bit of a mystery to me. I only heard some stories and stereotypes, so it was an amazing experience to see the reality of their lives and I was very honored that they gave me their trust and allowed me to stay with them and photograph.

TatiSpace: Your “Kucedra” project has been exhibited and published in a book. Can you tell us something more about it? How do you find this aspect of photography, when projects communicate to the public? Did the project have an impact?

Nick St.Oegger:That’s right, I published “Kuçedra” as a book first in 2018 and I have exhibited the work several times as well. For me it was very important that these photos go into the world in a physical way, not just on people’s screens. Publishing the book allowed me to raise awareness about the Vjosa, and the issues related to hydropower development on an international scale. I was lucky to partner with Patagonia and Save the Blue Heart of Europe campaign, so the book was distributed around the world, including to members of the European Parliament who have been trying to convince the Albanian government to save Vjosa.

Exhibiting the work has also been important, especially the exhibitions in Greece and Albania. For the Greeks it was a chance for them to see something of Albania, which is so close yet so far (a place many of them wouldn’t consider visiting). I had several people look at the photos and tell me “You know, these places could also be here. We are not so different” and this was very nice to hear, given some of the historical conflicts and tensions that exist between Greece and Albania.

It was so important for me to exhibit this work in Albania as well, so that everyday people can see the beauty of their own country in a way that they might not have previously done. It was really a nice experience to speak with people at the exhibition and to see that they have some connection to my work, to see how it makes them consider their country in a different way. That was very important to me, because I want my work to speak to Albanians. I don’t want it to be just for foreigners to see this “exotic” location. I hope that my work also connects with regular Albanians as well.

TatìSpace: Can you share something more about your next projects or exhibitions (if you prefer)?

Nick St.Oegger: I am planning to start writing another book about these last 8 years working in Albania. It will be a mixture of photos and personal stories from my time in the country. It’s something I’ve been wanting to do for some time. I also will have some more work related to hydropower, documenting areas where rivers have been destroyed by dams. So in a way I am still continuing with this work that I started years ago with “Kuçedra”, and it’s good to continue following this issue with hydropower and the effects it has on communities and the environment in Albania.

I hope to also continue with exhibitions, which unfortunately hasn’t been possible during the pandemic, but maybe as the situation improves it would be great to show more of my work both in Albania and abroad.

TatìSpace: Thank you very much for the interview and hope to see more of your work about Albania.

An overview to the main projects of Nick St.Oegger in Albania, “Kuçedra”and “The Lament of the Mountains”. More can be found in his website: www.stoeggerphotography.com

In “Kucedra” series, Nick St.Oegger explores thelast wild river of Europe: Vjosa (in Albania), and the proposed hydropower projects along its route that will alter the flow of the river, harming the rich and unique biodiversity within it and displacing thousands of people due to the creation of reservoirs. A key source of life for numerous endangered plant and animal species – many of which have disappeared from the rest of Europe’s rivers –Vjosa also holds cultural and economic significance for the rural communities along its banks, which once played an important role in Albania’s agricultural industry. Through landscapes, portraits and interior details, he portrays the environment of Vjosa in its natural state, as it faces the threat of being changed forever.

The Vjosa river near the Greek-Albanian border. Despite willingness to declare the river a national park in 2015, the Albanian government issued a contract to build a new hydropower dam at Poçem. The European Parliament has demanded the government to stop the plans for hydropower on the Vjosa, noting the environment damage it would cause. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

Interior Bënça. Locals in the village have protested a hydropower that will divert water from nearby Bënça tributary, which feeds into Vjosa. The loss of water from this river could have severe negative consequences for the agriculture. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

Ronja, a retired teacher in Kuta. Like many in the village, she does not hold title documents for her land, due to the administrative chaos that followed the fall of communism in the 1990s. This would complicate any attempts to claim compensation for land lost in the creation of the Poçem reservoir. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

Përmet, a cultural hub in southern Albania, well-regarded for its traditional music, art and slow-food practices. The Vjosa is integral to plans for growing the areas’s tourism industry, with the river seen as an important draw for rafting and kayaking excursions. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

Bridge over the Vjosa at Novosele, near the delta. Dams would increase riverbank erosion in downstream areas, meaning the already flood-prone delta region could see increasingly destructive flooding events in the future.

Abandoned petrol station on the road to Kuta. The road that links Kuta to the national highway is of poor quality, and has made shipping agricultural products impractical. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

Romina Mustafaraj, government representative for the village of Kuta. Romina has campaigned for infrastructure improvements in the village, including maintenance of flood-prevention systems, and repairs to the main road linking the village to the national highway. However, no investment has been made by the central government. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

Kuta, Village in Mallakaster county. During communism, Kuta was an important farming village, and went through significant development in the first decades of the regime. However, the area has been in decline since the end of communism in the 1990s. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

Mercedes in the village of Kuta, near the proposed Poçem dam. Around 3,000 people living in Kuta and the surrounding area could be affected if their land is flooded by a reservoir. This would mean the end of the area’s agricultural production, the only industry most have known. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

Farm in Kuta, near the proposed dam at Poçem. The reservoir created by the dam would permanently flood agricultural land in the area. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

“Without our land we have nothing”. Ylli and her family raise sheep and grow crops on land that would be flooded by a reservoir. There are few non-agricultural jobs in Kuta, meaning locals could have to relocate from lands their families have lived and worked on for generations. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

Fisherman’s shelter constructed between two communist-era bunkers in the Vjosa delta. Fishing along the river plays an important part in the local economy, and has already been negatively impacted by unregulated practices, such as dynamiting. Furthermore, damming the Vjosa would be detrimental for species such as the endangered European eel, which migrates along the river to spawn. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

Scientists traveling on the Vjosa near Poçem. Because Albania was isolated by the communist rule of Enver Hoxha, much of the river and its environment remain unexplored. An international team of scientists and NGOs has been compiling data on biodiversity and the river’s morphology, to use as part of a case for preserving the Vjosa. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

Dam construction site near Kalivaç. The project began in 2007 as a collaboration between Deutsche Bank and Italian businessman, Francesco Becchetti, but was stalled for several-years after charges of fraud and money-laundering were brought against Becchetti. He has denied these charges. The Albanian government nulled the contract and a new one was awarded to Turkish Ayen energy, who also hold the contract for the Poçem dam. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

Fields between Kalivaç and Kuta, which would be lost to flooding for the reservoir created by the Poçem dam. Electricity generation could come to a standstill within 30 years due to sediment built-up in the reservoir. This would require expensive and invasive dredging equipment to be brought into the area in order to clean debris. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

In “The Lament of the Mountains” photography series, Nick St.Oegger looks at ‘malësorët’of Kelmendi, a true pastoralist shepherd culture, and one of the last in Europe, whose economy is threatened by a dozen of dams planned to be constructed along alpine rivers. As government receives subsidies and loans from Western banks to solve the energy crisis with the construction of small scale hydropower plants, there is no public consultation for evaluating how it will affect the rich biodiversity and the lifestyle of highland shepherds. In Italy, Austria and Greece, UNESCO has recognized for protection the practice of pastoral shepherds, but there is no such status in Albania, which make their existence even more difficult.

Koprisht, Kelmend Region, Albania. Historically one of the most isolated regions in the country, most of Albania’s Northern mountains were never fully conquered during the Ottoman Empire’s 500year reign. The highland ‘malësorët’people have fiercely defended the region for centuries, operating under a strong system of tribal alliances. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

Gazmend Bikaj collects brush from the surrounding forests to construct a roof over a livestock enclosure in Koprisht, Kelmend region, Albania. Gazmend is a shepherd from Kalsa, a hamlet some 30km away, where he lives with his family most of the year. During the summer months they migrate to an encampment in the high pastures of Koprisht, taking a flock of sheep that belong to a farmer from the lowlands. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

During the summer, shepherds live in the high mountains in a temporary shelter called a ‘stan’. The structures are basic with an exposed dirt floor, stove and loft area for sleeping. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

Fonsi Bikaj moves a herd of sheep along the road from Tamarë to Koprisht, 35km away. Earlier in the day his father Gazmend had taken the sheep from their owner in the lowlands outside the city of Shkoder and walked with them into Kelmend. This process of transhumance has been practiced in the mountains for hundreds of years and risks dying out due to a decreasing population as well as threats from climate change and hydropower development. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

The site of a small scale hydropower plant in between the villages of Tamarë and Selcë, Kelmendi region, Albania. Small scale hydropower dams involve construction of several kilometers of pipeline that would divert the river underground, potentially drying out large sections of it and affecting the delicate biodiversity in the area. There are also concerns about the effect this would have on the local endangered trout population, which migrate along the river. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

A completed section of pipeline for a small scale hydropower plant near the village of Selcë, Kelmend region, Northern Albania. River water will be diverted into these pipelines to generate electricity at a power station downstream. Locals worry about the effects this will have on their access to water, which is critical for agriculture and raising livestock. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

Cousins Gjyste and Age Murçaj, in the village of Vukël, Kelmendi region, Albania. Emigration from the region has left a mainly ageing population, who often rely on family members living abroad for financial support. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

Anjeza Bikaj shakes out a tablecloth near the family’s summer encampment, Kelmendi region, Albania. Anjeza and her siblings take turns helping with household chores, milking the sheep and taking them into the surrounding mountains to graze. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

Albana Bikaj shares a moment of laughter with her sister Anjeza as the two make homemade playing cards at the family’s summer shelter in Koprisht, Kelmend region, Albania. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

Wilson Bikaj, one of Gazmend’s sons, help round up sheep in an enclosure in Koprisht, Kelmend region, Albania. The entire Bikaj family takes part in the process of caring for and grazing the sheep during the summer months. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

Rest near a café on the banks of the Cemi river, near Kozhnje. The region has seen an exodus of young people in recent years, with some 60% of the population of Kelmend emigrating, many to the United States. Job opportunities are limited and poverty levels remain high in the region, which has seen little development since the fall of the communist regime. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger

High pastures above the treeline near Lepushë, where several shepherds have their summer encampments. Historically the Albanian Alps have also been known as Bjeshkët e Nëmuna (the Accursed Mountains), owing to their isolation and difficult terrain. This has left the area largely untouched until recent plans to construct hydropower dams on several of the region’s rivers. Copyright © Nick St.Oegger